Linux S1E2: From UAF in km32 to IP Control or Arbitrary Read-Write

_Note: This is the second post in a series on Linux heap exploitation. It assumes that you have read the first part [0]. You can play with the exploit [1] yourself using the kernel debugging setup [2] published alongside this series.

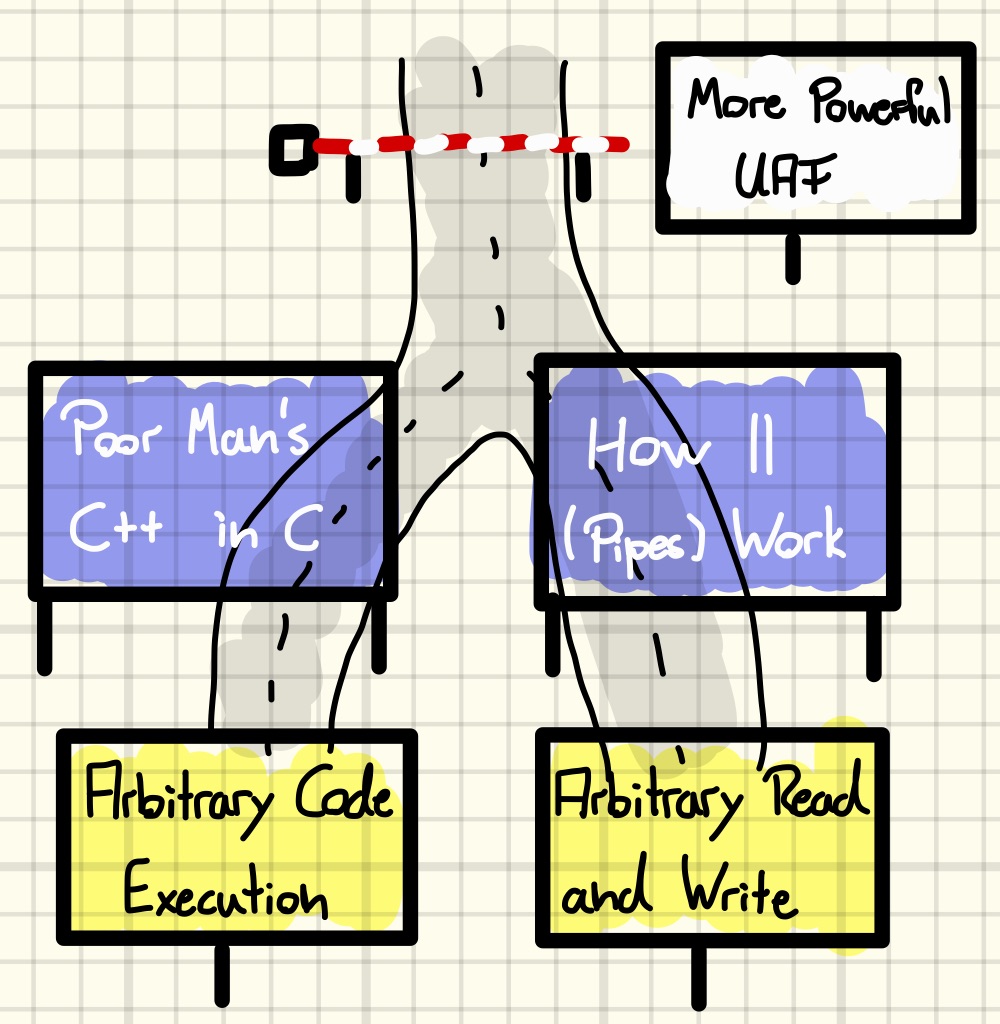

We concluded the previous post by abusing a use-after-free (UAF) in the kmalloc-32 cache to leak three kernel pointers. Now, we will use those leaks to cause another UAF, this time in the kmalloc-1k cache. By the end of this post, we will have learned how to turn this second, more powerful UAF either into kernel code execution via ROP or into an arbitrary read-write primitive via pipes.

Causing a More Powerful UAF

At the moment, we have a UAF in kmalloc-32 to play with. However, many standard techniques for constructing code execution or arbitrary read/write primitives require a UAF in a larger cache, e.g., the normal kmalloc-1k cache.

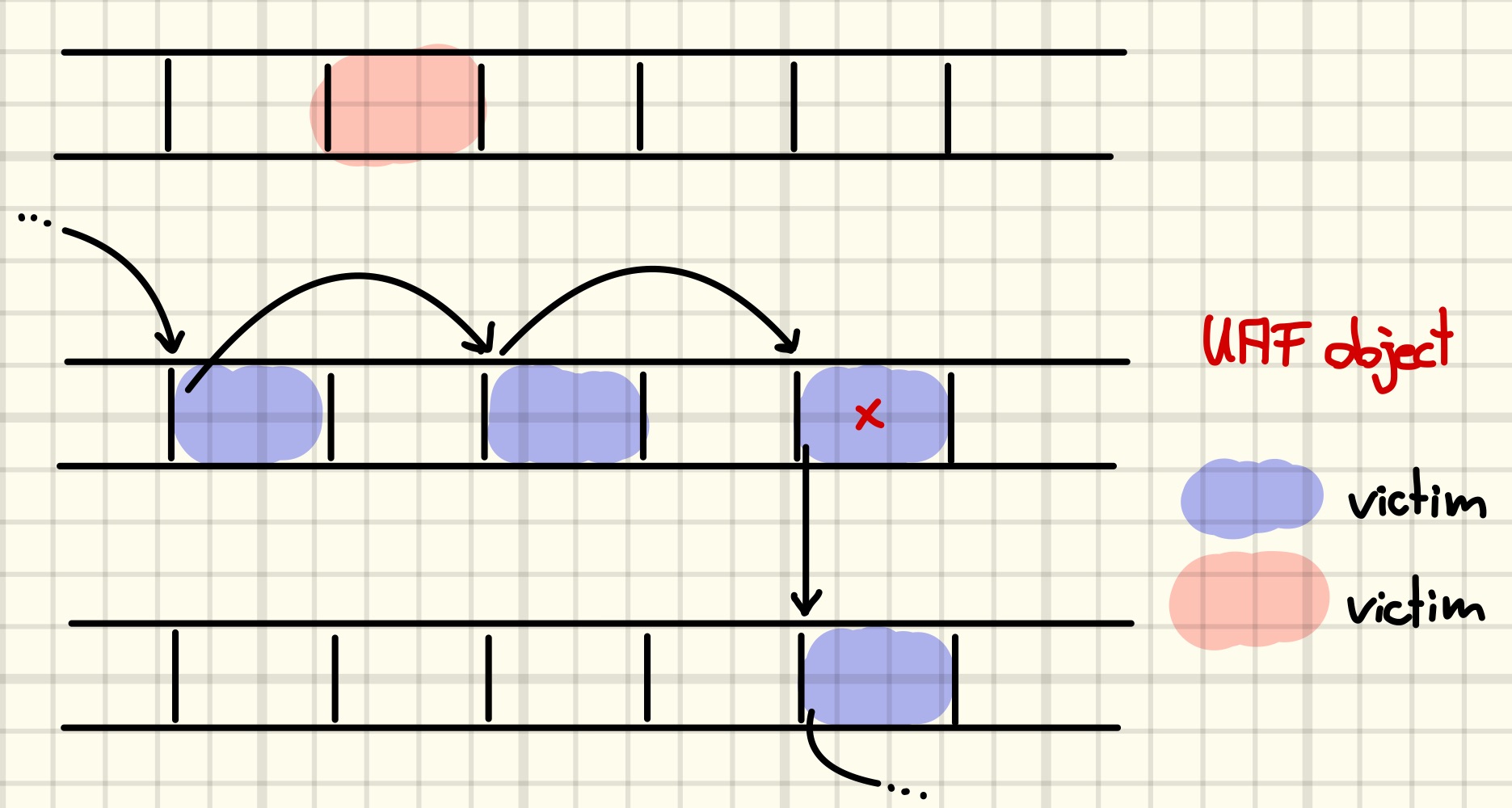

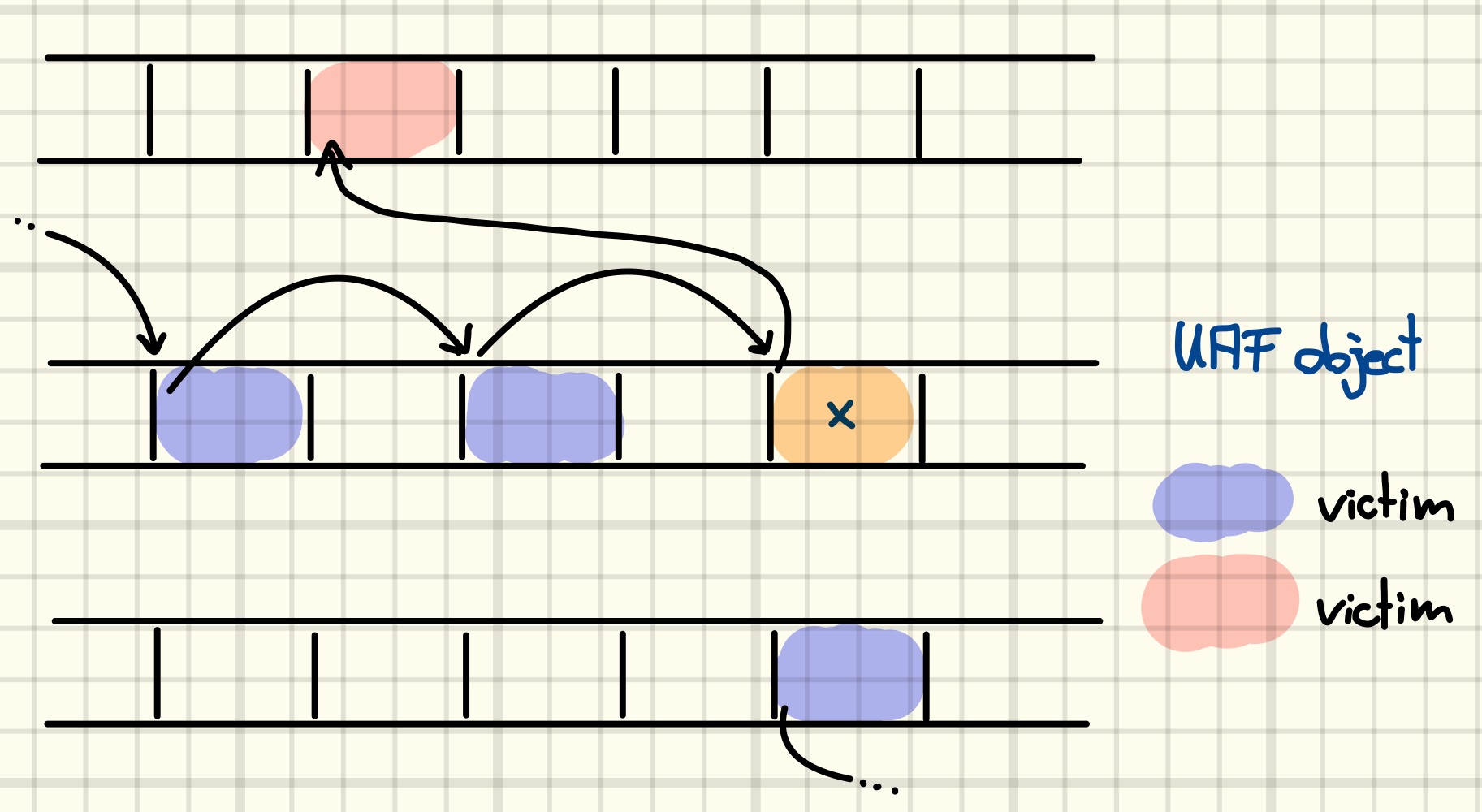

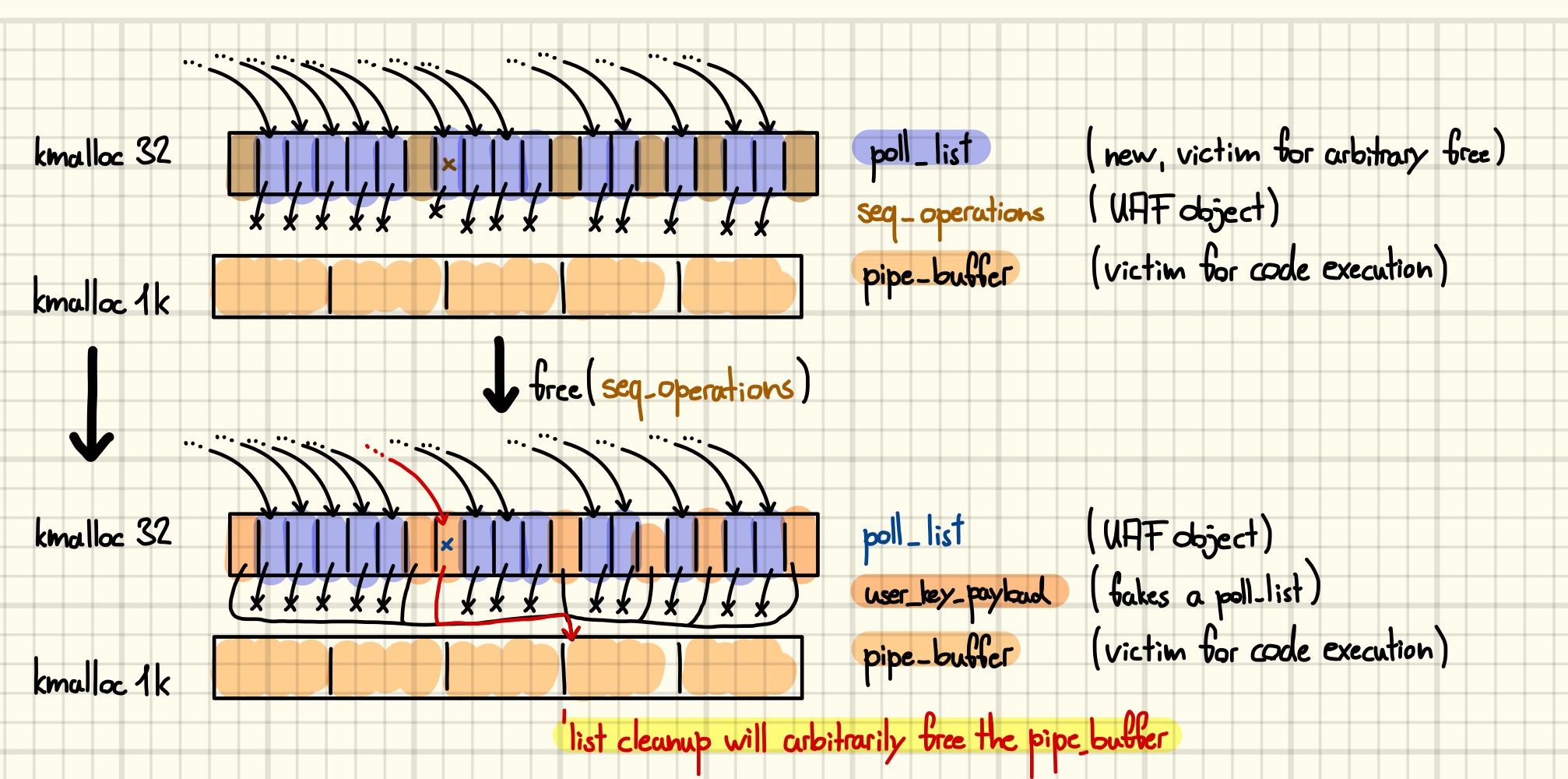

We begin by introducing the ansatz used to create another UAF from a conceptual standpoint before discussing the concrete realization. For starters, suppose that we can allocate a node in some singly linked list on the UAF slot in kmalloc-32, c.f., the figure below (red cross indicates existence of a dangling reference).

Causing a free of the dangling reference will now allow us to replace the node with another object. If we can control the contents of the reclaiming object, we can fake a list node to include an unsuspecting object at a known address in the list, c.f., the figure below.

Having read the previous blog post, you might have already guessed what will happen next: we trigger a list cleanup and arbitrarily free the unsuspecting object, i.e., we constructed the primitive to free an arbitrary pointer.

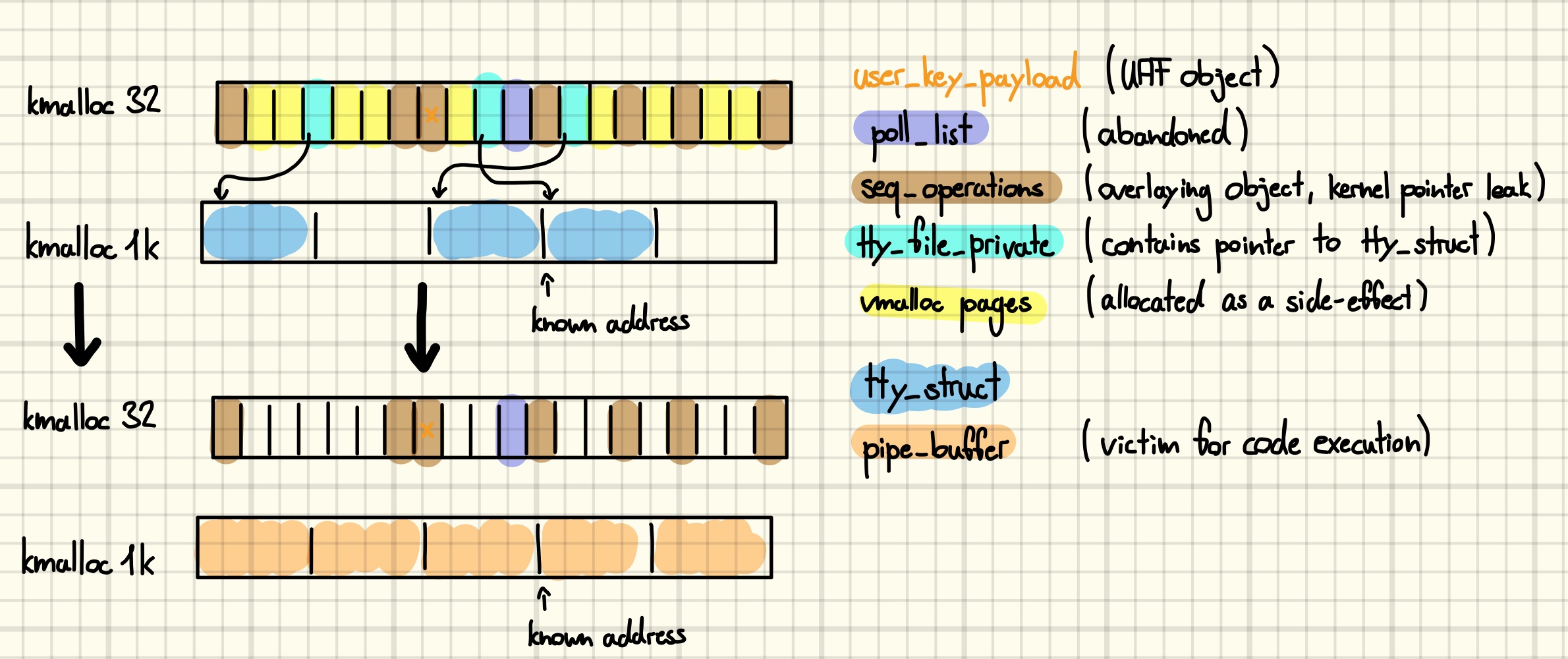

Realizing this idea will again be done by corrupting a poll_list. First, we must decide which kind of object we would like to free. Recall that we leaked the address of a slot in a kmalloc-1k slab that is currently occupied by a tty_struct. However, nothing prevents us from allocating another object in its place, and we are going to use this freedom to allocate an array of pipe_buffer structures at the known address. One such array is allocated whenever a new pipe is created [4]. We will elaborate on the semantics of these objects later, for the moment you must trust me that those make them interesting for exploitation. The next figure shows the desired memory transformation, starting from the memory layout we finished with at the end of the previous post.

Note: Experiments showed an increase in exploit stability when performing this step last. Conceptually this changes nothing, as long as the replacement happens before the pointer is freed, but it might throw you off when reading the code [5]. The decrease in stability makes sense as freeing the ttys is a rather noisy operation that, among other things, frees up many slots in the kmalloc-32 slab containing the UAF slot.

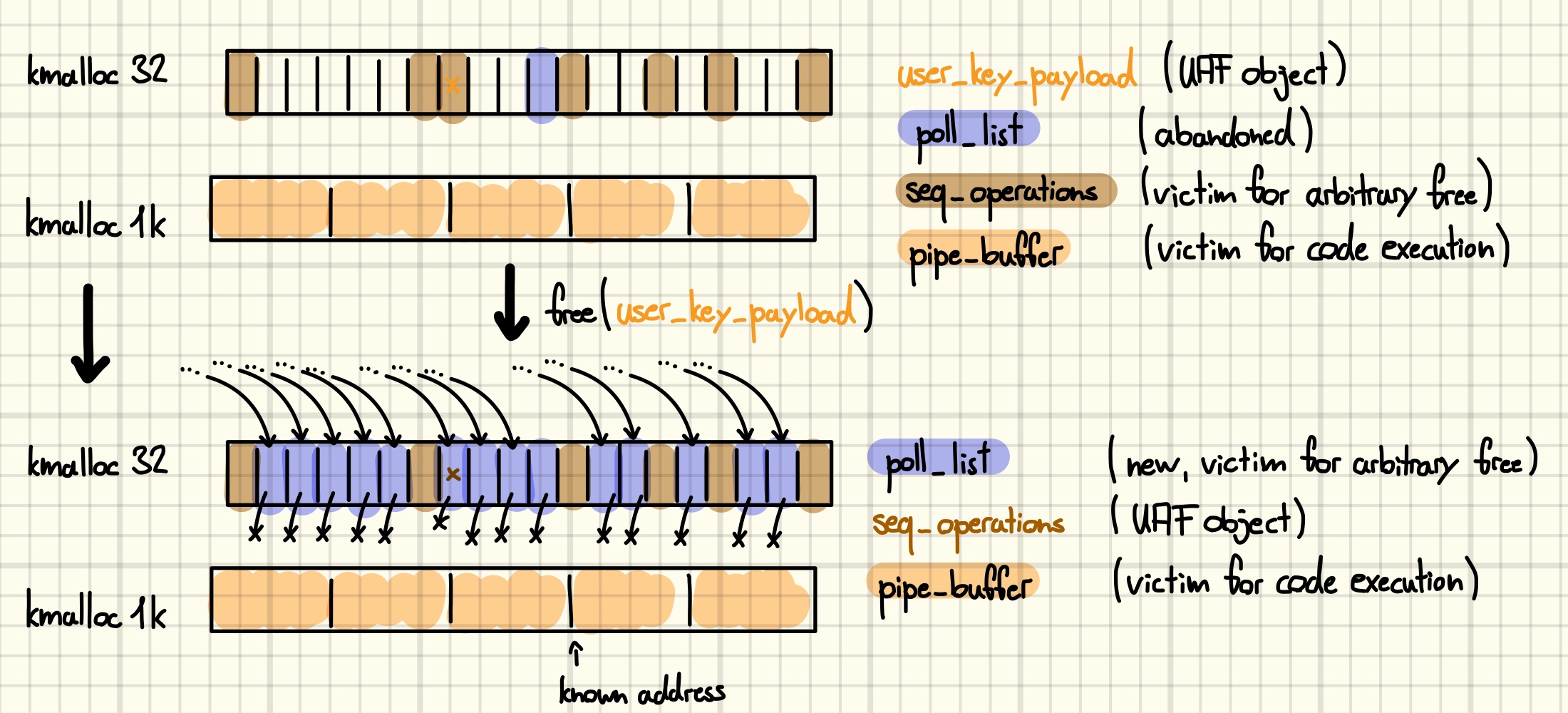

Next, we are going to free up the UAF slot and allocate a poll_list node on it. Recall that the slot is currently shared by a user_key_payload and a seq_operations structure. Furthermore, we do not know which seq_operations is occupying the UAF slot, however, we do know which key is corrupted. Thus, we avoid having to free many objects at once by using the key to free up the UAF slot. Spraying another round of poll_list lists reclaims the slot and leaves us with the following situation in kmalloc-32.

Aside: At this point, we meet a potential problem: user keys are freed via a Read Copy Update (RCU) callback [6]. RCU is a generic technique to improve the performance of shared read-mostly data structures. The idea is that readers enter a so-called RCU read-side critical section before accessing the data structure. While inside this section they are guaranteed that entries they obtain will remain valid, i.e., not be destroyed by someone who is concurrently manipulating the same data structure. This is achieved by delaying the actual destruction of an entry until all preexisting read-side critical sections are finished, i.e., after waiting for the so-called RCU grace period [7]. Regarding exploitation, this means that there is no point in starting to spray the heap right after an object we want to reclaim has been marked for freeing by RCU. Instead, we want to spray right after the object has been freed. Luckily, there is a system call that does nothing but wait until an RCU grace period has elapsed before returning, and we can use it to synchronize the start of our spray [8] [9].

Finally, what remains is to replace the poll_list allocated on the UAF slot with a fake one that points to the pipe_buffer array living in kmalloc-1k. For that purpose, we free all the seq_operations and use the setxattr technique to write the fake next pointer to the first QWORD of the vacant slots. However, leaving the UAF slot unoccupied for too long is not a good idea as it might lead to double frees, or unpredictable behavior in case the slot is reclaimed by an unrelated object. Thus, we “conserve” the fake pointer by allocating a user_key_payload, which leaves the first two QWORDs untouched.

Returning from the poll system call will now arbitrarily free a bunch of pipe_buffers. This is our more powerful UAF. Thanks for staying with me throughout this tedious sequence of steps. Now I owe you an explanation why it was worth going through this pain.

Aside: Some techniques are applicable without this extra sequence of steps. For example, we could trigger the destruction of the slab that contains the UAF slot, causing the backing page to be returned to the Page Allocator. Since the pages backing kmalloc-32 slabs are of order zero, i.e., a kmalloc-32 slab is made of 2^0 pages, it is simple to re-allocate the page as last-level user page tables. Accessing the UAF slot through a dangling pointer will now operate directly on user page table entries, which already sounds like a recipe for disaster. With a little work, this situation can be turned into a strong read-write primitive for physical memory that allows for trivial privilege escalation, e.g., by patching the kernel text [10] [11].

Abusing Fake C++ for Stack Pivots

There is a C coding pattern, which can be found in many large code bases, where an instance of a generic structure type might represent one of many more concrete objects. If this reminds you of runtime polymorphism you are well on track. The poster child example in Linux is probably struct file. There is one for every open file in the system, and as you probably heard a hundred times, for user space “everything is a file”. This leaves the kernel with a situation where an instance of a file might represent a hardware timer, a BPF map, a development board, an end of a pipe, a network connection, or … an ordinary file on an ordinary hard disk using an ordinary ext4 filesystem.

To manage this situation, the generic structure has two key fields

struct file {

...

const struct file_operations *f_op;

...

void *private_data;

...

} __randomize_layout

where the first one, i.e., f_op, is defined as another rather generic struct, this time full of function pointers.

struct file_operations {

...

ssize_t (*read) (struct file *, char __user *, size_t, loff_t *);

ssize_t (*write) (struct file *, const char __user *, size_t, loff_t *);

...

int (*mmap) (struct file *, struct vm_area_struct *);

...

int (*open) (struct inode *, struct file *);

...

} __randomize_layout;

High-level code, e.g., in the virtual file system layer, will perform the C equivalent of a virtual call to dispatch operations to the lower-level routines that know how to perform them for the given kind of file.

ssize_t vfs_read(struct file *file, char __user *buf, size_t count, loff_t *pos)

{

...

if (file->f_op->read)

ret = file->f_op->read(file, buf, count, pos);

...

}

Aside: When reading kernel code those virtual calls are a frequent source of frustration as one oftentimes does not know which handler will be invoked for the object one is interested in. In such situations the rescue comes in the form of my favorite command: trace-cmd [12]. For example, we can use it to easily resolve the read handlers for various kinds of files.

$ trace-cmd record -p function_graph -g vfs_read --max-graph-depth 2 -F cat /proc/sys/kernel/modprobe

cat-4497 [001] 13316.293420: funcgraph_entry: | vfs_read() {

...

cat-4497 [001] 13316.293421: funcgraph_entry: + 28.696 us | proc_sys_read();

cat-4497 [001] 13316.293450: funcgraph_exit: + 29.772 us | }

$ trace-cmd record -p function_graph -g vfs_read --max-graph-depth 2 -F cat /tmp/hax

cat-4519 [009] 13401.049113: funcgraph_entry: | vfs_read() {

...

cat-4519 [009] 13401.049114: funcgraph_entry: 0.444 us | shmem_file_read_iter();

cat-4519 [009] 13401.049114: funcgraph_exit: 1.158 us | }

$ trace-cmd record -p function_graph -g vfs_read --max-graph-depth 2 -F cat /home/archie/bar

cat-4539 [005] 13493.856387: funcgraph_entry: | vfs_read() {

...

cat-4539 [005] 13493.856389: funcgraph_entry: 0.981 us | ext4_file_read_iter();

cat-4539 [005] 13493.856390: funcgraph_exit: 2.857 us | }

$ trace-cmd record -p function_graph -g vfs_read --max-graph-depth 2 -F cat /sys/fs/bpf/maps.debug

cat-4364 [004] 221.406352: funcgraph_entry: | vfs_read() {

...

cat-4364 [004] 221.406352: funcgraph_entry: 0.863 us | bpf_seq_read();

cat-4364 [004] 221.406353: funcgraph_exit: 1.689 us | }

The subsystem code that creates the objects will usually set the vtable pointer to a subsystem-internal constant variable that specifies the functions that know how to operate on the file {1}. Furthermore, it usually stores a pointer to an object that holds more specific information in the private_data member {2}, which makes the information available to the handlers as their parameters always include a pointer to the file object that they were invoked on. Yes, this smells a lot like subclassing.

const struct file_operations pipefifo_fops = {

...

.read_iter = pipe_read,

.write_iter = pipe_write,

...

};

int create_pipe_files(struct file **res, int flags) {

struct inode *inode = get_pipe_inode();

struct file *f;

...

f = alloc_file_pseudo(inode, pipe_mnt, "",

O_WRONLY | (flags & (O_NONBLOCK | O_DIRECT)),

&pipefifo_fops); // {1}, sets f->f_op = &pipefifo_fops

...

f->private_data = inode->i_pipe; // {2}, struct pipe_inode_info *

...

}

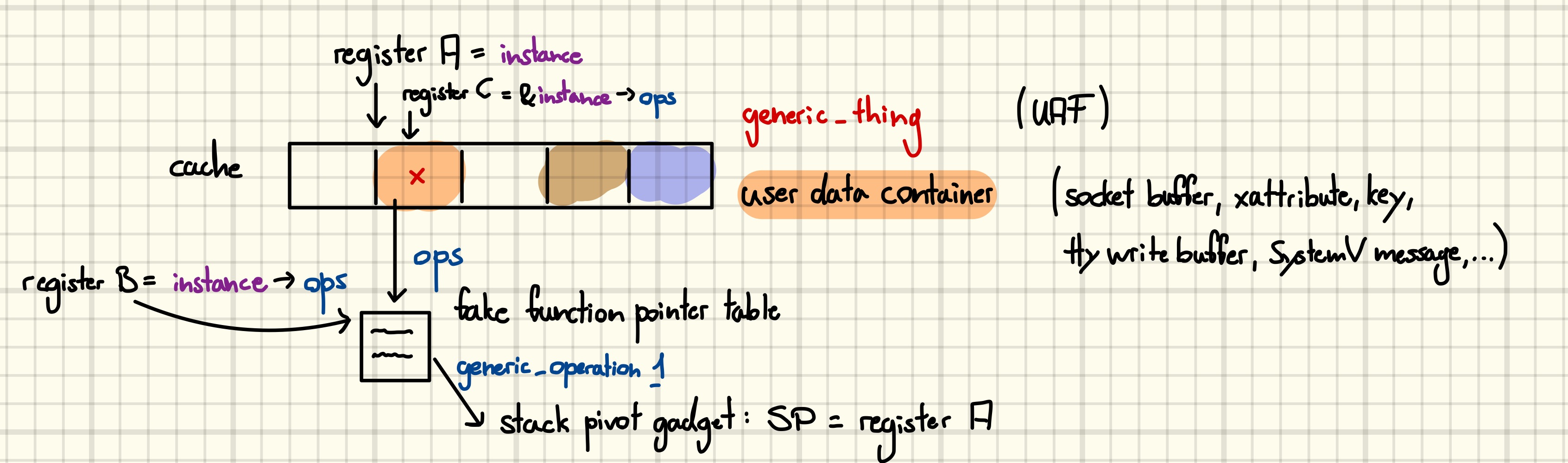

Okay, but why care about object-oriented ideas in a programming language more than twice my age? We care because essentially all kernel exploits that gain code execution do so by corrupting an object that has a vtable with the intention of hijacking a virtual call. The idea is relatively straightforward: arbitrarily free an object at a known address and replace it with user-controlled data. The fake object’s vtable will point back into the controlled data, where the virtual call will finally find the address of a stack pivot gadget. Pivoting the stack into controlled data is feasible as at least the register providing the ‘self’ argument must point to the corrupted object, however, usually more registers will contain useful values.

There are a few properties that we would like the victim object to have:

- Faking it should be easy. If the object is used in complicated ways before the virtual call happens the bar of creating a convincing fake rises, which we want to avoid as we are lazy.

- Pivoting should be easy. At the point where we take instruction pointer (IP) control the CPU registers should be full of pointer into controlled data such that we do not have to spend ages looking for ROP/JOP gadgets.

- Reclaiming it should be easy. While it is possible to reclaim objects across cache boundaries by taking a detour to the Page Allocator, it is better if the victim object is allocated in the same cache as an easily sprayable user data container.

Luckily, our array of

pipe_buffers meets all those requirements.

When the last reference to a pipe is released, it will be destroyed. During that process, the code will eventually iterate over all pipe_buffers and call their destructors. This is where we will take IP control.

void free_pipe_info(struct pipe_inode_info *pipe) {

...

for (i = 0; i < pipe->ring_size; i++) {

struct pipe_buffer *buf = pipe->bufs + i; // dangling pointer

if (buf->ops) // {1}

pipe_buf_release(pipe, buf);

}

...

}

static inline void pipe_buf_release(struct pipe_inode_info *pipe,

struct pipe_buffer *buf) {

const struct pipe_buf_operations *ops = buf->ops;

buf->ops = NULL;

// `buf` points into our data and we control value of `ops`

ops->release(pipe, buf);

}

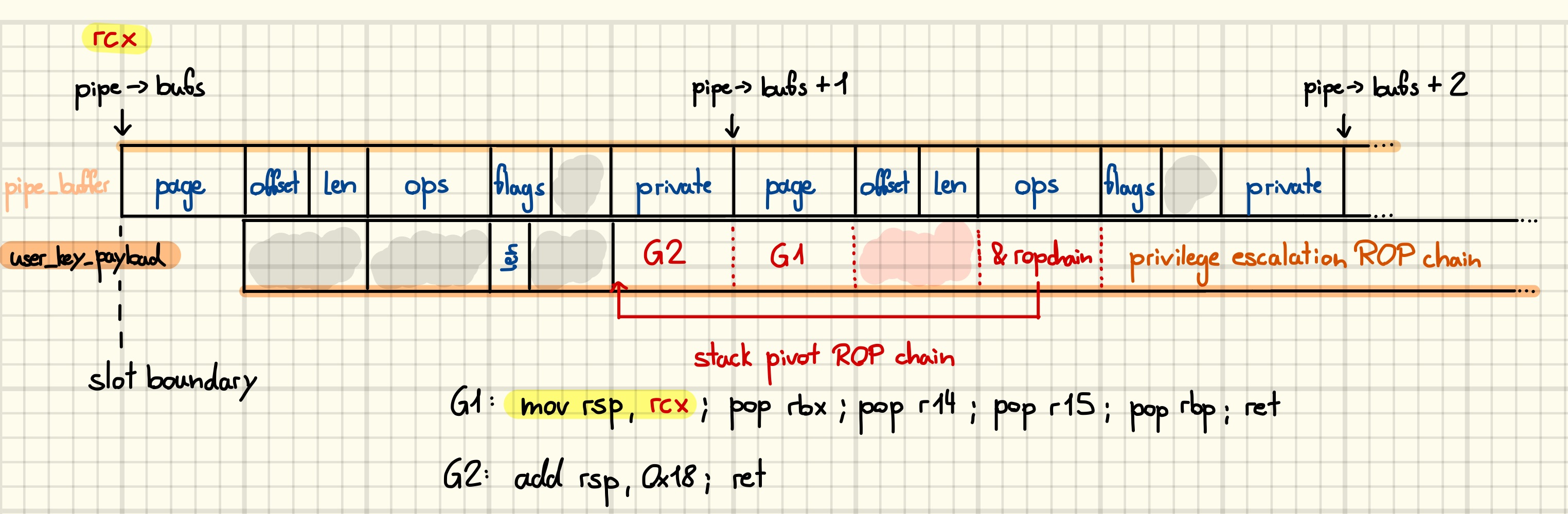

Crafting our payload, however, requires examining what the compiler made of that code.

mov rcx, qword ptr [rbx + 152] # rcx = pipe->bufs

movsxd rdx, ebp

lea rsi, [rdx + 4*rdx]

mov rdx, qword ptr [rcx + 8*rsi + 16] # rdx = (pipe->bufs+i)->ops

test rdx, rdx

je 0xffffffff812f0d9f <free_pipe_info+0x2f>

lea rax, [rcx + 8*rsi]

add rax, 16 # rax = &(pipe->bufs+i)->ops

lea rsi, [rcx + 8*rsi] # rsi = pipe->bufs+i

mov qword ptr [rax], 0

mov r11, qword ptr [rdx + 8] # r11 =(pipe->bufs+i)->ops->release

mov rdi, rbx

call 0xffffffff81e02300 <__x86_indirect_thunk_r11> # retpoline "call r11"

As we can see in the above listing, rcx, rdx, rax, and rsi hold interesting values. Equipped with that knowledge we can start crafting our ROP payload. Since we allocate our data as user_key_payload objects we must not forget to account for the structure header, which is unfortunately not under our control. Consequently, a naive overlay would result in the len field overlapping with the first buffer’s ops field, making the condition {1} pass on an uncontrolled value. However, as the SLUB allocator performs only limited alignment checks on allocations and frees, we can adjust the relative position by performing a misaligned free, causing the loop to skip the first buffer.

The first gadget pivots the stack to the first QWORD of controlled data, while the second one skips over the part that was used to pivot the stack and leaves us at the start of the ROP chain responsible for privilege escalation.

Doing kernel ROP sounds cool, but in practice, it has several drawbacks that make it unattractive. For example, portability is hampered by the need to manually search for new ROP gadgets and control flow integrity (CFI) might make life harder on some platforms. Therefore, we will now discuss how to construct a primitive that will allow for a data-only privilege escalation.

Aside: While crafting my first kernel ROP chain I noticed that some things are different from in user land exploitation. Let me elaborate on two of them here. First, the kernel is a self-modifying program. Thus, what you get when disassembling the image’s text section is not what you will find in executable memory at runtime. Fortunately, I read about this before it first happened to me, and thus I quickly figured out what was going on [13]. Be advised to dump the executable mappings at runtime and use them as input for ROP gadget finders. The second thing is already visible in the assembly listing above, but it took me way longer to figure it out. In fact, I have not read it anywhere yet. To mitigate against spectre family attacks, the kernel might use so-called retpolines when performing indirect control flow transfers [14]. Retpolines are semantically equivalent to jmp REG or call REG operations, which makes them interesting for building ROP chains, but manifest themselves as calls to fixed addresses in the disassembly. As I am used to discarding gadgets that end in calls to fixed addresses when building user land ROP chains this oversight led to me missing many potentially useful gadgets.

Abusing |’s for Arbitrary Read and Write

Despite using pipelines in every second shell command, it was not until exploring the Dirty Pipe vulnerability that I had a look into their implementation [15] [16]. In essence, a pipe is a circular, in-kernel buffer that can be read from and written to by user space through file descriptors. For example, when executing a pipeline, the parent shell creates a pipe and hands the disparate ends to the subshells that execute the commands, which use it to connect their stdin and stdout streams.

$ strace -e pipe2,dup2 -f sh -c "cat /tmp/hax | cat"

pipe2([3, 4], 0) = 0

strace: Process 4975 attached

[pid 4975] dup2(4, 1) = 1

strace: Process 4976 attached

[pid 4976] dup2(3, 0) = 0

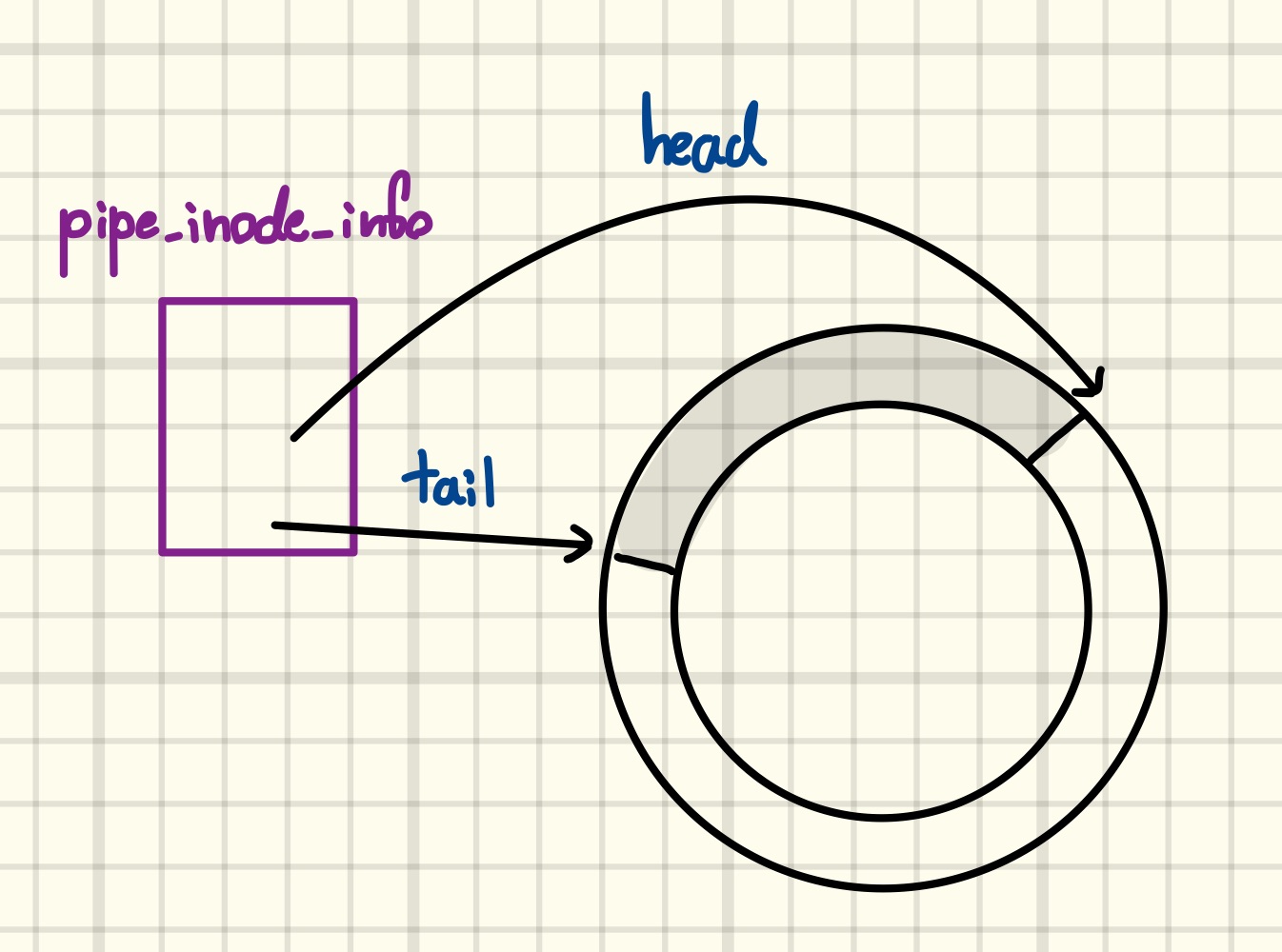

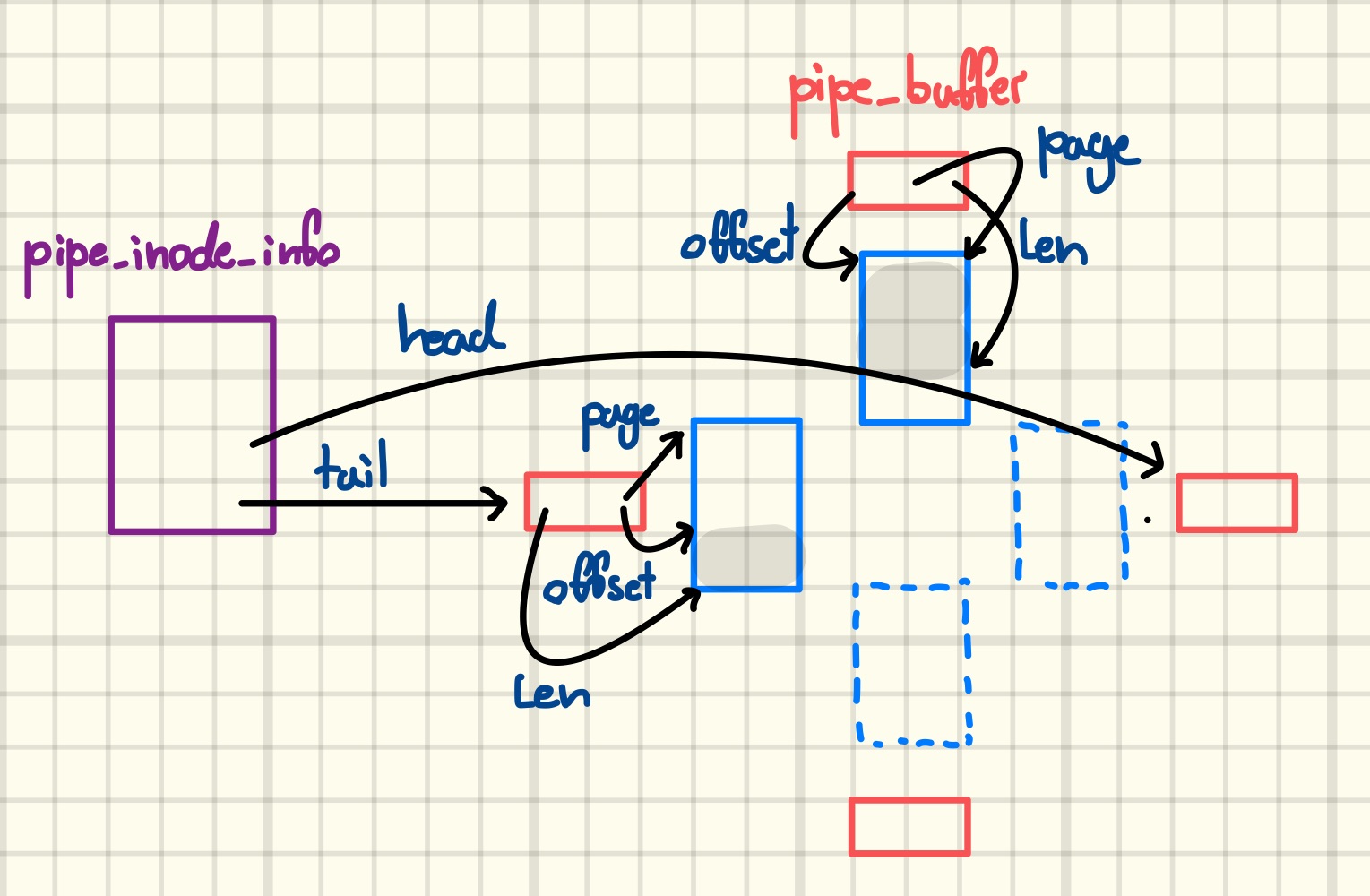

For each pipe, the kernel maintains a pipe_inode_info structure that, among other things, tracks the positions in the circular buffer that data will be read from or written to the next time user space interacts with the pipe. The next figure shows a partially filled pipe.

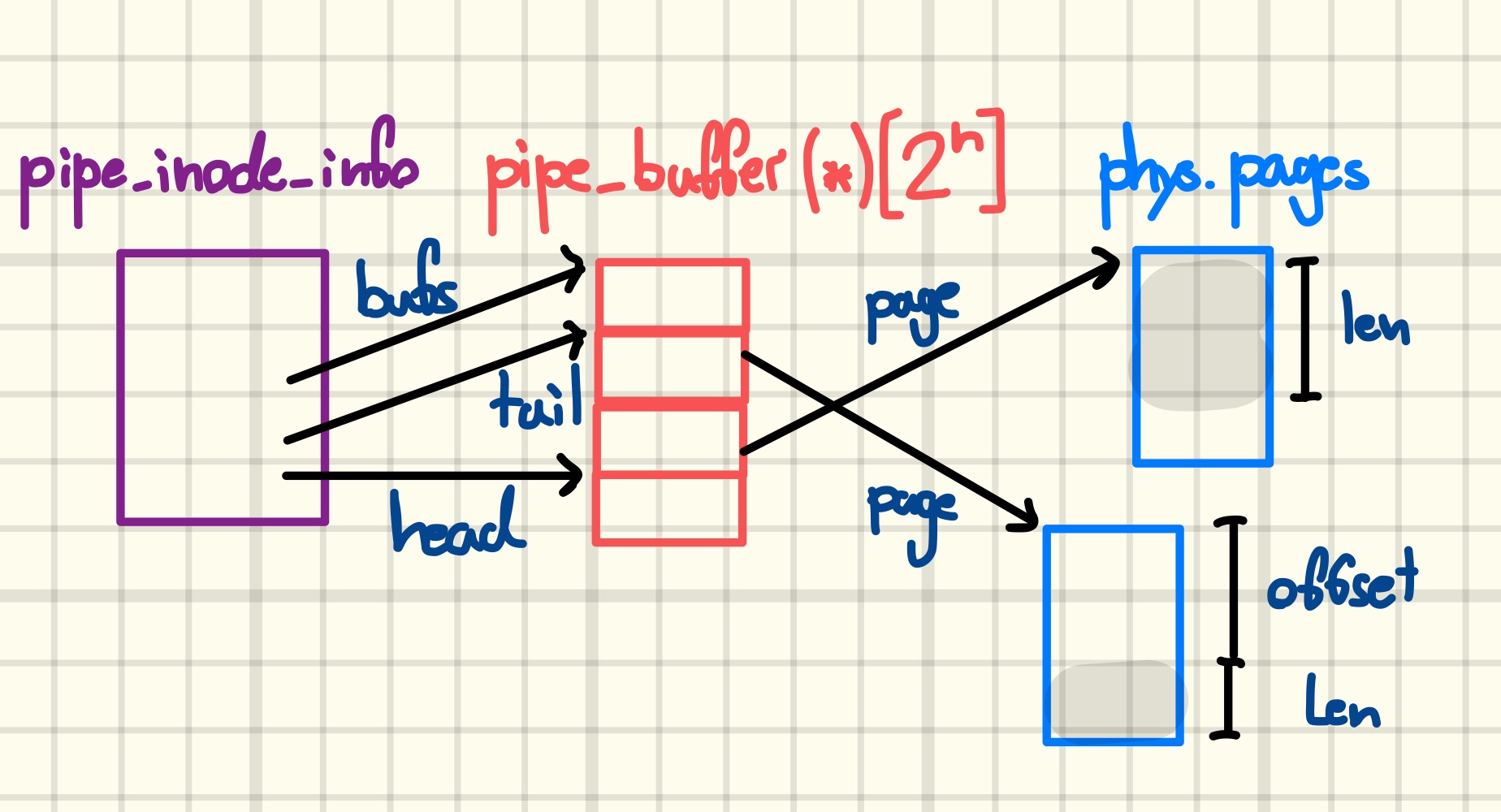

However, the above picture is grossly oversimplified, and understanding the exploitation technique requires digging a bit deeper into the implementation. In particular, the circular buffer is realized through multiple non-contiguous pages of memory, each of which is managed by a pipe_buffer structure. The pipe_buffer contains a pointer to the page describing the underlying memory, as well as the offset and length of the user data currently stored on the page. As we can see in the next figure, this indirection allows minimizing the pipe’s memory footprint.

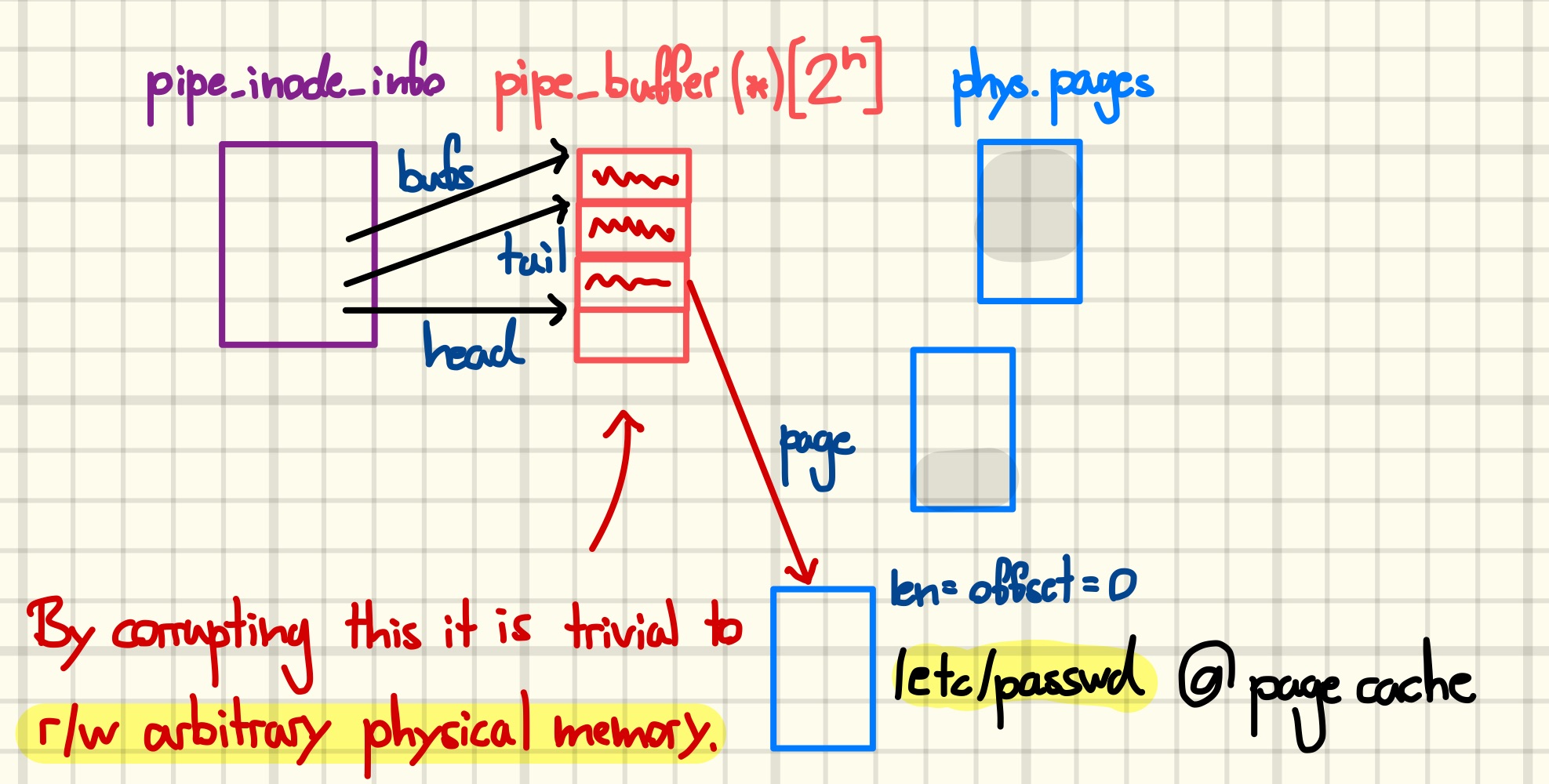

Finally, we need to make one last adjustment to our mental picture, namely that the kernel stores the pipe_buffers in a heap-allocated array, a pointer to which is kept in the bufs member of pipe_inode_info. The integers head and tail are indices into this array, and circularity is implemented by masking them with the array length, aka. ring_size, which is a power of two, minus one before each access. It is exactly an array of this kind that we arbitrarily freed earlier.

Given that background, there is not much creativity involved in devising a way to abuse the UAF to create an arbitrary read-write primitive. By setting the page, offset, and len fields of the tail buffer before performing an i/o operation on the pipe, we can read from or write to arbitrary RAM-backed physical addresses.

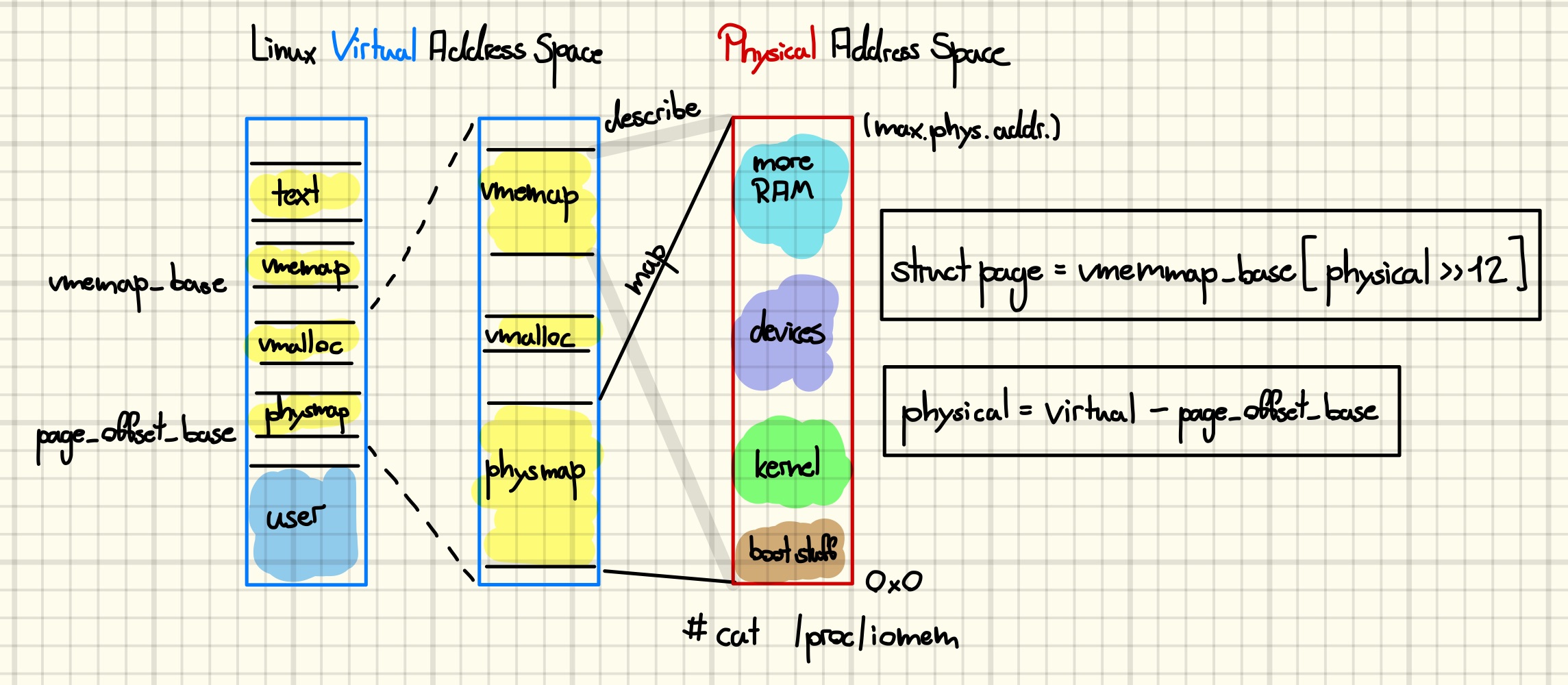

The conversion between physical, virtual, and page addresses required for this technique involves two distinct regions in the kernel’s virtual memory space: the direct map and the vmemmap region. The former is, as the name suggests, a direct map of all physical memory of the system, while the latter is an array of page structures describing this memory, c.f., the figure below for a simplified illustration.

Until now, it was sufficient to corrupt the arbitrarily freed object once, e.g., to replace it with a fake object for stack pivoting. However, we plan to scan substantial amounts of physical memory, and thus we need to be able to edit the pipe_buffer array repeatedly. Performing thousands of free and reclaim races sounds like an excellent recipe for crashing the kernel. Thus, another approach is needed. Ideally, we want a user data container without any headers whose contents we can update without reallocating it. Luckily, tty write buffers give us just that primitive [17].

Aside: There is another way to solve this problem by using a second pipe. The first pipe is corrupted once such that the pipe_buffer at tail references the page containing the pipe_buffer array. Then, we splice the whole buffer into a second pipe. Now, the catch is that pipes keep one scratch page for performance reasons, and through careful manipulation of the second pipe we can make sure that its scratch page is always the one containing the first pipe’s buffer array [18].

Aside: Besides the page, offset, and len members, there is one more thing we need to initialize in the pipe_buffer if we want to use it for writing: the flags. In particular, we need to set the PIPE_BUF_FLAG_CAN_MERGE flag to indicate that it is okay to “append” subsequent writes to this buffer. Yes, that is the flag that caused all the Dirty Pipe trouble and I still forgot to initialize it.

Aside: After our sprays we will own plenty of pipes and ttys, however, we do not know which pipe is corrupted and which tty is responsible for it. We can use the FIONREAD ioctl on the pipe, which returns the number of bytes that can be read from it, together with unique write buffer payloads to figure out the pairing [19].

Kernel Address Space Layout Randomization (KASLR) Revisited

Before we can proceed, we need to take a step back and take a closer look at the leaks we collected in the previous blog post.

Recall that we leaked a pointer to a page as well as a pointer to a heap-allocated tty_struct. The former points into the kernel’s vmemmap-region, while the latter points into a RAM-backed section of the kernel’s direct map, also known as page-offset, region, which maps all of physical memory [20].

Both regions are randomized independently at kernel startup with a granularity of one GiB, which is the size of memory covered by a Page Upper Directory (PUD) entry [21]. Due to constraints on the layout of virtual memory, the entropy of the randomization is about 15 bits according to a comment by the developers. Furthermore, the region’s ordering must remain unchanged. Note that the randomized regions may start above or below their nonrandomized base addresses, which are 0xffffea0000000000 and 0xffff888000000000, respectively [21].

Without further assumptions, it is only possible to extract the base address of a memory region from a valid pointer if we know that the pointer’s base offset cannot be larger than the randomization granularity. This immediately implies that, in the general case, it is not possible to extract the page_offset_base from a valid pointer into the direct map. At least on systems with more than one GiB of RAM.

However, for the leaked page pointer the situation is less certain. As the size of struct page is 64 bytes, a vmemmap region of size one GiB can describe 64 GiB of physical memory. On my laptop with 32 GiB of RAM, for example, the size of the physical memory space is 34 GiB, which would make every valid page pointer splittable into the Page Frame Number (PFN) and the vmemmap_base.

Assuming that we can split the leaked page pointer, the pipe-based physical read primitive can be used to search for the kernel image. According to the documentation of the RANDOMIZE_BASE configuration option, the virtual and physical base addresses of the kernel image are randomized separately [22]. Consequently, our virtual kernel image leak is useless for this task. Furthermore, we know that the kernel can be anywhere between 16 MiB and the top of physical memory, which we take to be 64 GiB, with a worse-case granularity of 2 MiB [23] [24].

This results in about ~30k possible base addresses. The number of read operations can be reduced further by incorporating that the kernel text section alone is usually already larger than 10 MiB. Thus, by reading only every fifth possible physical base, we can derandomize the kernel in about 6k reads, at worst. Afterwards, reading the page_offset_base variable from the data section finally allows us to convert back and forth between virtual and physical addresses.

Aside: If we cannot split the leaked page pointer, we might as well throw a coin, i.e., start searching the kernel base either towards lower or higher physical addresses. As this might lead to invalid accesses beyond the vmemmap region we introduce a 50% probability of failure at this point.

Aside: While developing the original version of my exploit, I did not pay sufficient attention to this topic. I simply assumed that the leaked physmap pointer is always splittable, which was only true since ASLR was disabled. However, as we saw above the pipe-based exploit flow can still work by first finding the kernel image. Nevertheless, it would still be nice to have ASLR enabled in the development stage to avoid making such mistakes in the future. For debugging, randomization of the kernel image, both physical and virtual, is a pain. Unfortunately, as far as I know, there is no way to selectively enable the randomization of the vmemmap, vmalloc, and page-offset regions. We can help ourselves around that restriction by disabling ASLR on the kernel command line, which will make the boot stub decompress the kernel at the physical address 0x1000000 and maps it to the virtual address 0xffffffff81000000 [25] [26]. After jumping into the decompressed kernel, we can use the debugger to edit the boot parameters to pretend that ASLR is enabled, which will result in the randomization of the other memory regions [27]. In the future, it would be nice to automate debugging with full ASLR enabled.

Finding our Task Struct

With that technicality out of the way, we can start to explore physical memory. An obvious target for a data-only privilege escalation is the task_struct of the exploit process, which is the structure that the kernel uses to track all kinds of information needed to run the task. In order to find it, we can leverage the fact that it includes the process’ comm, which is a 16-byte name that we can set using a prctl command. Setting the comm prior to searching reduces the risk of finding a stale task struct of a dead tread. Additionally, it is recommended to perform additional sanity checks on each instance of the name found during the memory scan to ensure that it indeed belongs to our task descriptor, and not to, for example, the page cache entry of our executable or our process’ address space.

Wrap Up

Constructing an arbitrary free primitive from our UAF in kmalloc-32 allowed us to cause a UAF on a pipe_buffer array. Afterwards, we explored two ways to capitalize on this. First, we reclaimed the freed slot with a user_key_payload that contained a fake pipe_buffer whose destructor was manipulated to trigger a stack pivot into a ROP chain stored in the same buffer. Second, we reclaimed the slot with a tty write buffer, which gave us the freedom to repeatedly overwrite the pipe_buffer. With a little bit of background on how pipes work, this primitive enabled us to scan physical memory to locate our task descriptor.

In the next post, we will recollect why we are doing this whole exercise. On a conceptual level, the goal is to elevate the privileges of our process, however, as we will discover many mechanisms act together to define what is commonly referred to as a process’ privileges. Our task will be to identify the parameters we need to tweak to perform the privileged action we need to win the challenge, i.e., reading a file in the root users’ home directory. Furthermore, we will learn how to easily experiment with different privilege escalation approaches to develop stable exploit routines, using both, the code execution and the read write primitive.

References

[0] https://blog.eb9f.de/2023/07/20/Linux-S1-E1.html

[1] https://github.com/vobst/ctf-corjail-public

[2] https://github.com/vobst/like-dbg-fork-public

[4] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/fs/pipe.c#L806

[5] https://github.com/vobst/ctf-corjail-public/blob/master/sploit.c#L478

[6] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/security/keys/user_defined.c#L128

[7] https://pdos.csail.mit.edu/6.S081/2022/readings/rcu-decade-later.pdf

[8] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/kernel/sched/membarrier.c#L470

[9] https://github.com/lrh2000/StackRot

[10] https://yanglingxi1993.github.io/dirty_pagetable/dirty_pagetable.html

[11] https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com/2021/10/how-simple-linux-kernel-memory.html

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JRyrhsx-L5Y

[13] https://a13xp0p0v.github.io/2021/02/09/CVE-2021-26708.html

[14] https://support.google.com/faqs/answer/7625886

[15] https://dirtypipe.cm4all.com/

[16] https://lolcads.github.io/posts/2022/06/dirty_pipe_cve_2022_0847/

[17] https://github.com/0xkol/badspin

[18] https://www.interruptlabs.co.uk/articles/pipe-buffer

[19] https://github.com/vobst/ctf-corjail-public/blob/master/libexp/rw_pipe_and_tty.c#L77

[20] https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/v5.10/x86/x86_64/mm.html

[21] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/arch/x86/mm/kaslr.c#L64

[22] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/arch/x86/boot/compressed/misc.c#L413

[23] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/arch/x86/Kconfig#L2122

[24] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/arch/x86/Kconfig#L2162

[25] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/arch/x86/Kconfig#L2064

[26] https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.10.127/source/arch/x86/boot/compressed/misc.c#L341

[27] https://github.com/vobst/like-dbg-fork-public/blob/d2d50a5bce3986fe30cd43bf8595825dd7266324/io/scripts/gdb_script_partial_kaslr.py