LSMs Jmp'ing on BPF Trampolines

Back in 2001, the Linux Security Module (LSM) subsystem made its way into the mainline kernel. Almost 10 years ago, in September 2014, the modern BPF virtual machine (VM) landed in the tree. In late 2019, KP Singh proposed a patchset that facilitates the creation of modules for the former that run on the latter - Kernel Runtime Security Instrumentation (KRSI) was born.

But how does kernel control flow transfer in and out of the VM at the security checkpoints? Originally, this question was raised while developing a memory forensics tool for detecting BPF-based malware, but it quickly became a great learning experience about the internals of the two subsystems. In this post, we will seek an answer to that first question, and then use it to develop the module that detects such hooks in memory images.

However, before we jump into assembly code, let’s briefly recap on LSMs and BPF.

Linux Security Modules

By default, Linux implements discretionary access control. For example, the owner of a resource is free to grant others access to it.

$ chmod 444 .ssh/id_rsa

This is potentially problematic, e.g., on multi-user systems where users have different security clearances. To implement other access control policies, e.g., mandatory access control, organizations like the National Security Agency (NSA) had to maintain their own kernel patches.

At the 2001 Kernel Summit in San Jose, California, the NSA’s Peter Loscocco presented their Security Enhanced Linux (SELinux); but the patchset was not merged. However, one year later at the Kernel Summit in Ottawa, Chris Wright presented the patch that should later become the Linux Security Module subsystem.

Citing its documentation:

The LSM framework includes security fields in kernel data structures and calls to hook functions at critical points in the kernel code to manage the security fields and to perform access control. It also adds functions for registering security modules. An interface /sys/kernel/security/lsm reports a comma separated list of security modules that are active on the system. link

The framework is intended to be generic enough to facilitate enforcing of a wide range of security policies by writing a kernel module that uses those two primitives. But writing kernel modules is hard, mistakes might have catastrophic consequences, and the binary blobs only run on the kernel they were compiled for - but fortunately there is…

Further reading: Linux Security Modules: General Security Support for the Linux Kernel

Modern BPF

BPF is a VM inside the Linux kernel. It is used for running programs in a sandboxed environment within the kernel context.

Programs can be written in C, Rust or even high-level scripting languages. They are compiled to BPF bytecode, which can be dynamically loaded into the kernel where it is statically verified before being compiled to native code. Thus, running BPF programs is safe, in the sense that a programming mistake won’t crash your kernel, as well as low overhead. Furthermore, type information included in modern kernels is used to relocate programs before loading, eliminating the need for compilation on the target system.

By now, the VM is used in many different kernel subsystems, like networking, tracing, security, cgroups or scheduling. In an effort to provide a safer kernel programming environment, it is actively being extended with new features.

Further reading: BPF and XDP Reference Guide

Kernel Runtime Security Instrumentation (KRSI)

This patchset added the option to implement the security callbacks as programs for the BPF VM. For illustration purposes, we are going to use a very simple security module that aims to detect and prevent two common malware behaviors. You can find the full source code here.

Fileless Executions

Using a remote code execution exploit, an attacker might be able to

compromise a process running on a victim’s machine. Downloading and

executing a second stage payload without touching the filesystem might

be desirable due to security measures preventing the creation of (executable)

files or to minimize forensic artifacts. While userland exec is a

well-known technique, it is much more convenient to use Linux’s memfd

API. To detect such events, we can write the following BPF program and

attach it to the bprm_creds_for_exec security hook.

SEC("lsm/bprm_creds_for_exec")

int BPF_PROG(bprm_creds_for_exec , struct linux_binprm* bprm)

{

int nlink = 0;

char comm[BPF_MAX_COMM_LEN] = { 0 };

char path[BPF_MAX_PATH_LEN] = { 0 };

nlink = bprm->file->f_path.dentry->d_inode->__i_nlink; // [1]

bpf_d_path(&bprm->file->f_path, path, sizeof(path));

LOG_INFO("path=%s nlink=%d", path, nlink);

if (!nlink) {

bpf_get_current_comm(comm, sizeof(comm));

LOG_WARN("fileless execution (%s:%lu)", comm, bpf_ktime_get_boot_ns());

bpf_send_signal(SIGKILL); // [2]

return 1; // [3]

}

return 0;

}

This hook is called early during the exec system call and it receives the file that the process wants to execute. At [1] we get the number of hard links to this file. If it is zero, we deny the execution [3] and queue a fatal signal for the process [2]. The latter is necessary since the hook is called before the syscall’s point-of-no-return, after which all errors are fatal.

Note: You can use the

memfd_exec

program to test this hook. It also allows you to experiment with the

differences between executing a script starting with #! and an ELF binary.

Self-Deletion

Less sophisticated malware might simply try to go memory-resident by

deleting its executable on disk. We can write another BPF program

and attach it to the inode_unlink security hook in an attempt to

prevent this behavior.

SEC("lsm/inode_unlink")

int BPF_PROG(inode_unlink, struct inode* inode_dir, struct dentry* dentry)

{

struct task_struct* current = NULL;

char comm[BPF_MAX_COMM_LEN] = { 0 };

const struct inode *exe_inode = NULL, *target_inode = NULL;

int i = 0;

target_inode = dentry->d_inode; // [1]

LOG_INFO("target_inode=0x%lx", target_inode);

for (i = 0,

current = bpf_get_current_task_btf(),

exe_inode = current->mm->exe_file->f_inode; // [2]

exe_inode && i < BPF_MAX_LOOP_SIZE;

i++,

current = BPF_CORE_READ(current, parent),

exe_inode = BPF_CORE_READ(current, mm, exe_file, f_inode))

{

bpf_probe_read_kernel(&comm, sizeof(comm), ¤t->comm);

LOG_INFO("exe_inode=0x%lx comm=%s", exe_inode, comm);

if (target_inode == exe_inode) { // [3]

bpf_get_current_comm(comm, sizeof(comm));

LOG_WARN("self-deletion (%s:%lu)", comm, bpf_ktime_get_boot_ns());

bpf_send_signal(SIGKILL);

return 1;

}

}

return 0;

}

We attach this program to the inode_unlink hook, which is called each

time a process attempts to delete a file. The callback receives the

parent directory as well as the directory entry of the file that is to

be deleted. First, the dentry is used to obtain the underlying inode

[1]. Then, the loop reads the inode of the file that the process (or

any of its ancestors) is executing [2].

Finally, by comparing the two [3] we can attempt to detect

self-deletions.

Note: This program is flawed in many ways. First, it breaks updates, e.g., when the package manager updates systemd’s executable. Furthermore, it is easy to bypass, e.g.,

- The parent deletes its child’s executable and exits. Then, the child gets reparented and deletes the parent.

- Schedule removal through another task, e.g.,

cronorsystemd. - Use the

prctlsyscall to set the exe file. - Scripts that are run by an interpreter are unaffected.

- Using

io_uring’s asynchronous unlink requests in combination with a dedicated kernel thread for processing them might (not tested) also be an option.

BPF Trampolines: The glue between C and BPF

Now that we got ourselves a small BPF-based security module to play with, we can examine how it works under the hood.

Reaching the tramp

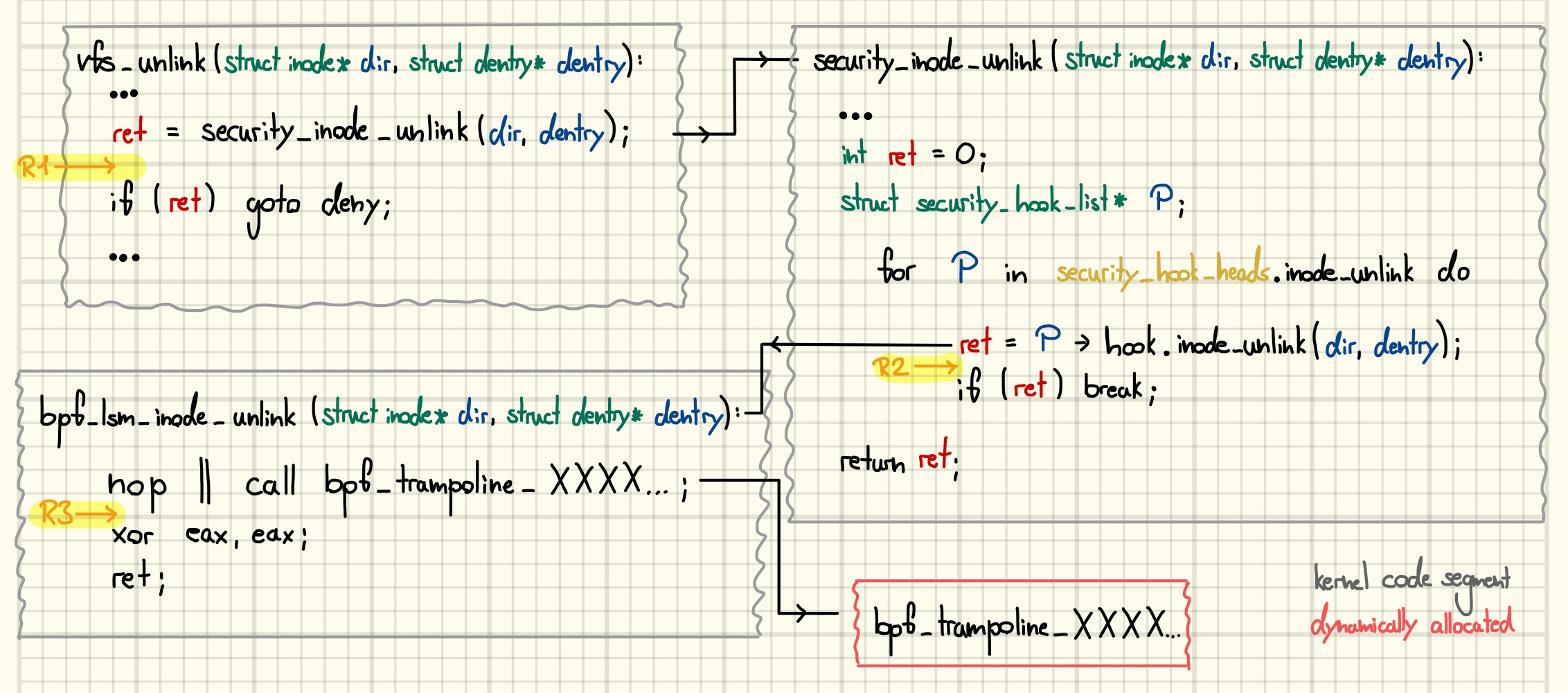

Let’s start by looking at the part of the infrastructure that is statically compiled into the kernel. Figure 1 gives an overview of the code path leading up to our BPF program.

At selected places, the kernel calls functions starting with

security_. For example, the vfs_unlink function calls

security_inode_unlink and aborts if it returns a nonzero value.

LSM hooks are meant to provide a higher level of abstraction than

system calls; thus it makes sense to pace the gatekeeper call at

a choke point in the virtual file system (VFS) which may operations

must pass, independently of their entry point into the kernel and the

type of object they are operating on.

Each of those call sites has its own member in the global

security_hook_heads structure. The security_inode_unlink function

uses its member to traverse a list of all registered callbacks, calling

them one by one. As soon as one of them returns a nonzero value it

aborts and propagates the value back to the caller.

There are numerous ways how we can find out where the indirect calls

lead us. For example, we can use trace-cmd with the function graph

tracer to record a trace of the functions called during an unlink

system call.

$ touch /tmp/hax && sudo trace-cmd record -p function_graph \

--max-graph-depth 4 -g do_unlinkat -n "*interrupt*" -n "*irq*" \

-n "capable" -n "*__rcu*" -n "*_spin_*" -v -e "*irq*" -e "*sched*" \

-F /bin/rm /tmp/hax \

&& trace-cmd report trace.dat && sudo trace-cmd reset

...

rm-8004 [011] 17857.021621: funcgraph_entry: | security_inode_unlink() {

rm-8004 [011] 17857.021621: funcgraph_entry: 0.129 us | bpf_lsm_inode_unlink();

rm-8004 [011] 17857.021622: funcgraph_exit: 0.436 us | }

...

Alternatively, we can debug the kernel on a guest VM and set a breakpoint, e.g., on the function we suspect to be called. Looking at the backtrace confirms the observation:

...

(remote) gef➤ b bpf_lsm_inode_mkdir

Breakpoint 2 at 0xffffffff81230d80: file ./include/linux/lsm_hook_defs.h, line 126.

(remote) gef➤ c

...

(remote) gef➤ bt

#0 bpf_lsm_inode_mkdir (dir=0xffff8880053f63a0, dentry=0xffff888005799480, mode=0x1ed) at ./include/linux/lsm_hook_defs.h:126

#1 0xffffffff814c56d0 in security_inode_mkdir (dir=0xffff8880053f63a0, dentry=0xffff888005799480, mode=0x1ed) at security/security.c:1298

#2 0xffffffff8130488e in vfs_mkdir (mnt_userns=0xffffffff82e4e920 <init_user_ns>, dir=0xffff8880053f63a0, dentry=0xffff888005799480, mode=0x1ed) at fs/namei.c:4029

#3 0xffffffff81304a02 in do_mkdirat (dfd=0xffffff9c, name=0xffff8880075b1000, mode=0x1ed) at fs/namei.c:4061

#4 0xffffffff81304b7d in __do_sys_mkdir (pathname=<optimized out>, mode=<optimized out>) at fs/namei.c:4081

...

However, as we can see, the function usually does absolutely nothing.

(remote) gef➤ x/5i $rip

=> 0xffffffff81230d80 <bpf_lsm_inode_mkdir>: endbr64

0xffffffff81230d84 <bpf_lsm_inode_mkdir+4>: nop DWORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

0xffffffff81230d89 <bpf_lsm_inode_mkdir+9>: xor eax,eax

0xffffffff81230d8b <bpf_lsm_inode_mkdir+11>: ret

It exists for the sole purpose of being ftrace attachable! You might

have spotted the nop instruction at the very beginning: this one is

just reserving some space which allows the ftrace framework

to divert control flow by dynamically patching the kernel text.

We can see the patching machinery at work by placing a read-write

watchpoint on the nop’s address before attaching our program. It is hit multiple times during the attachment process, and when everything is

done, the nop is replaced by a call to a BPF trampoline.

The Tramp

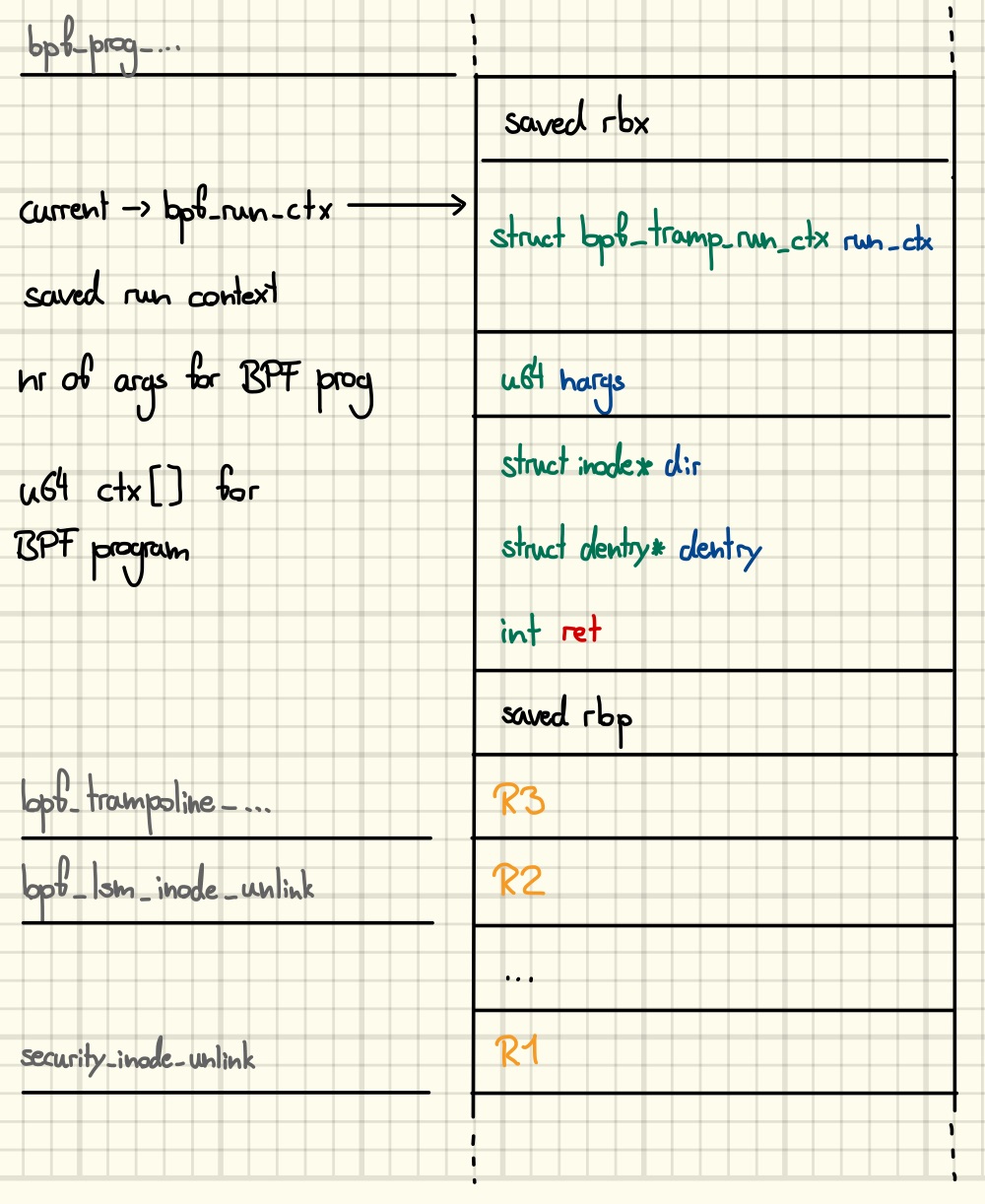

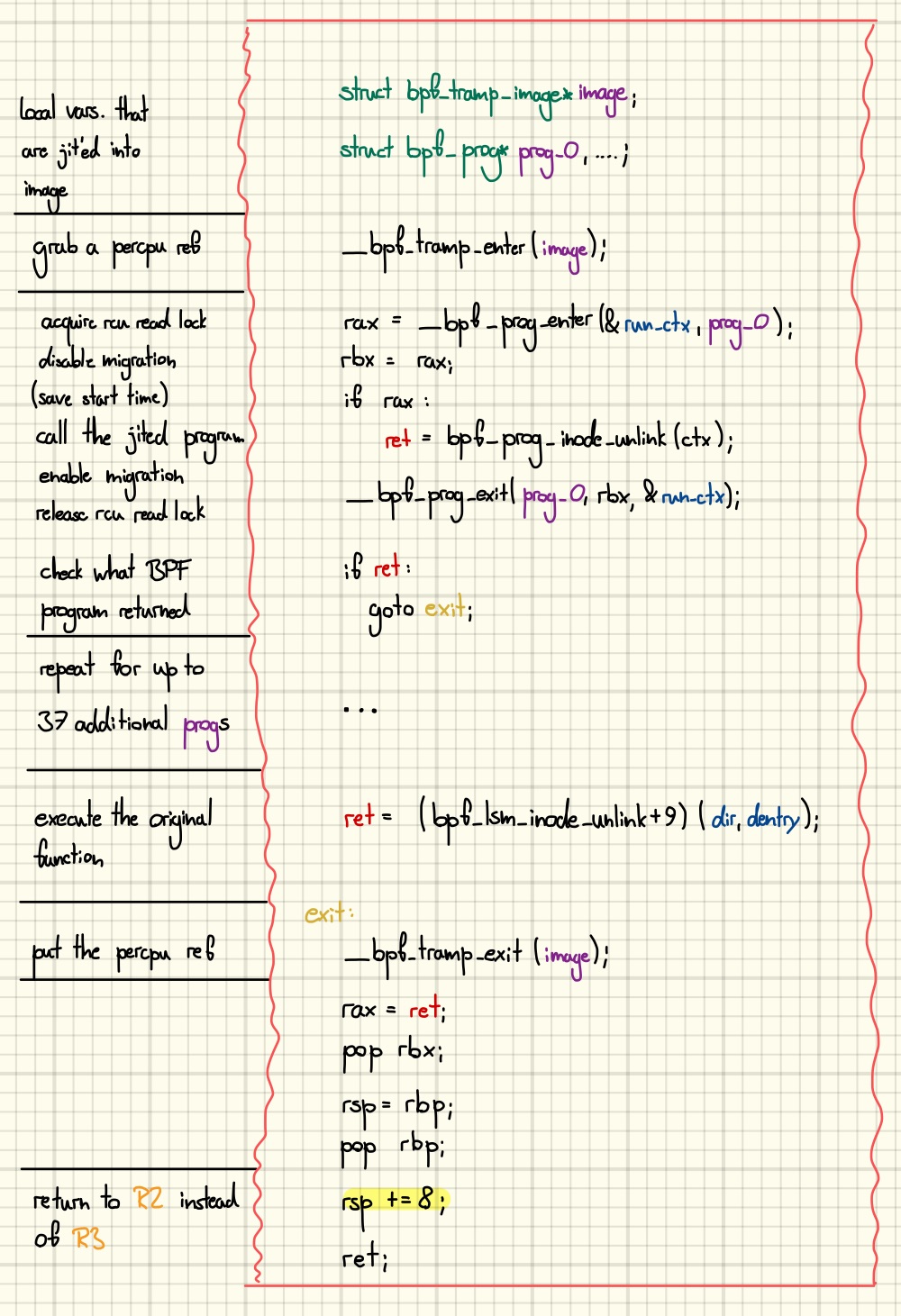

BPF trampolines are the architecture-dependent glue that connects native kernel functions to BPF programs. Currently only arm64 and x86 support the generation of BPF trampolines. Figures 2 and 3 show the stack frame and code of the generated trampoline, respectively.

Some values are burned into the trampoline upon generation; this

includes pointers to its metadata-holding struct bpf_tramp_image

as well as the struct bpf_prog of each program it leads up to. Local

variables are stored in the trampolines stack frame, most importantly

the read-only context ctx received by the BPF programs lives on this

stack.

The execution of the trampoline begins by grabbing a percpu reference to itself. Probably to indicate to other code which CPUs are currently using the trampoline. (Question: Is it really a percpu ref? Would be strange to get it while migration is enabled.)

Now comes the part where the trampoline calls into the jit-compiled BPF programs one by one, handing each program a pointer to the stack-allocated context holding the directory and the directory entry of the file to be deleted as well as the return value of the previous BPF program. While a BPF program is running it enters a read-copy-update (RCU) read-side critical section and disables migration to other CPUs. Optionally, it might also measure the execution time of the BPF program.

As soon as a program returns a nonzero value, the trampoline stops invoking

other programs and directly goes to its exit routine. Otherwise, it

calls the original function, i.e., bpf_lsm_inode_unlink, for its

side effects and return value once all BPF programs are finished.

Upon exit, the trampoline drops the ref to itself and returns directly

into the security_inode_unlink function through an extra lowering of

its stack pointer, propagating either the return value of the last BPF

program or that of the attached function.

Aside: You probably already guessed that the utility of ftrace and BPF trampolines are not limited to realizing KRSI.

In fact, we already saw another use of the ftrace framework: it’s the

machinery that drives trace-cmd. If you’d strace it, you would see

that it’s doing most of its magic by reading and writing files in

tracefs, the user space interface of ftrace. Furthermore, ftrace can

also be used by kernel modules to install callbacks into their code.

BPF trampolines on the other hand are used to jump into all kinds of BPF programs, not only LSM-related ones. Numerous flags are controlling their generation, and the outcome we described above is just one combination of those. For instance, you could also generate trampolines that cannot skip the original function and simply return to it, or trampolines that call BPF programs after the original function was executed by the trampoline.

Digging Through Memory Dumps

Now that we are equipped with some background knowledge, we can get back to the original question: Given a memory dump of a system can we reconstruct which BPF LSM hooks were active?

For this part, we’re going to use Volatility3 as a memory forensics framework and implement our feature as a plugin. You can find the source code here. However, the techniques are not tied to a specific framework in any way.

First, we have to find out which hooks are active. For that

purpose we can simply disassemble all the bpf_lsm_ stub functions

and check if their ftrace nops are replaced by a call. This gives us

the active hooks and the corresponding addresses of the executable

trampoline images.

Next, we can figure out which programs belong to a given image. There are at least two approaches that immediately come to mind: disassemble the trampolines and extract the compiled-in addresses of the program code and their corresponding metadata structs, or query higher-level abstractions like BPF link objects.

While the first approach is less susceptible to anti-forensics it

suffers from dependence on trampoline code generation. Since we already

know which hooks are active it’s safe to look for the program information

at places that are easier to manipulate, like the link_idr which

contains all BPF link objects in use. If we don’t find a corresponding

program there it’s considered suspicious, and we will raise an alert.

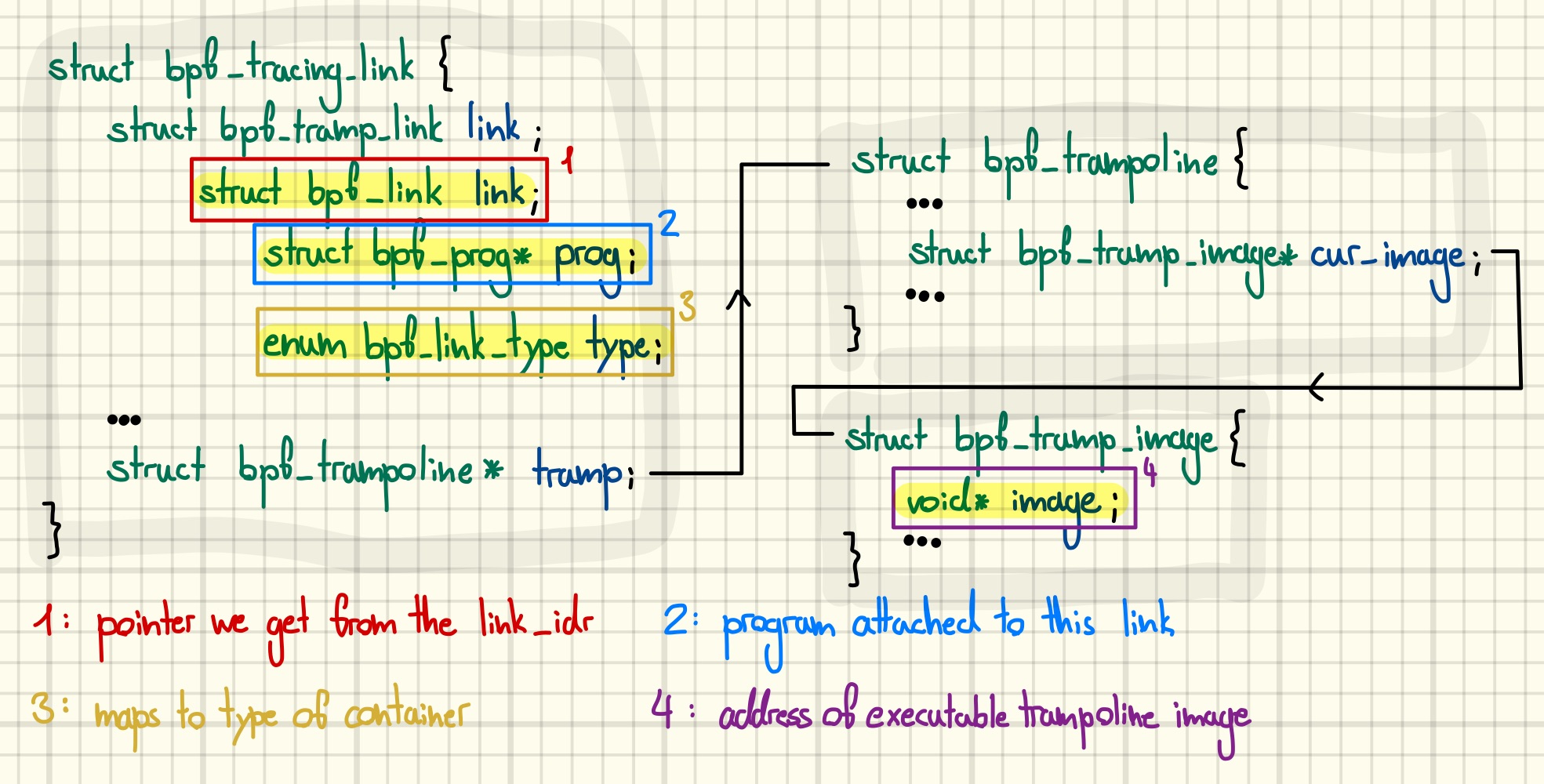

Figure 4 gives an overview of how BPF link objects can be used

to match trampoline images to links. Iterating the link_idr gives

us bpf_link objects. The link type maps directly

the type of the container structure. Thus, if it indicates a tracing

link we can pivot to the outer struct and use its trampoline member to

get the address of the executable trampoline image that the link’s

program is attached to.

Putting it all together, we can find all active BPF LSM hooks as well as all programs attached to them. You can find the full Volatility plugin code that implements the above approach in our BPF plugin suite on GitHub. Running it against a memory image of a system that uses our toy LSM correctly reports activity on two hooks.

./vol.py -f /io/dumps/mini_lsm_w_dummy.elf -v linux.bpf_lsm

...

LSM HOOK Nr. PROGS IDs

bpf_lsm_bprm_creds_for_exec 2 16,18

bpf_lsm_inode_unlink 1 19

Note that we have added a second program to bprm_creds_for_exec

in order to cover the case where more than one program is attached to a

single hook. You can now use the

program IDs with other plugins like bpf_listprogs to continue your

investigation. The memory image can be downloaded

here

and the symbols are provided

here.

Wrapup

In this post, we learned about LSMs, a cornerstone of building high-security Linux systems, and their programmability through modern BPF. On the way we met two core parts of Linux’s tracing infrastructure: ftrace and BPF trampolines. In the end, we leveraged this knowledge to build a memory forensics tool capable of detecting a subtle way in which malware might infect a system.

References

[1] “Building a Security Tracing Utility To Snoop Into the Linux Kernel.” https://lumontec.com/1-building-a-security-tracing

[2] “ChromeOS: Noexec File System Bypass Using Memfd.” https://bugs.chromium.org/p/chromium/issues/detail?id=916146

[3] “Commit: bpf: Introduce BPF Trampoline.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/torvalds/linux/commit/fec56f5890d93fc2ed74166c397dc186b1c25951

[4] “eBPF: Block Linux Fileless Payload ‘Malware’ Execution With BPF LSM.” https://djalal.opendz.org/post/ebpf-block-linux-fileless-payload-execution-with-bpf-lsm/

[5] “Elixir: arch/x86 arch_prepare_bpf_trampoline.” [Online]. Available: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/latest/source/arch/x86/net/bpf_jit_comp.c#L2128

[6] “FOSDEM 2020: Kernel Runtime Security Instrumentation LSM+BPF=KRSI,” Jan. 02, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://archive.fosdem.org/2020/schedule/event/security_kernel_runtime_security_instrumentation/

[7] “Google Help: retpoline.” [Online]. Available: https://support.google.com/faqs/answer/7625886?hl=en

[8] “KPsingh‘s Kernel Tree.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/sinkap/linux-krsi/blob/patch/v1/examples/samples/bpf/lsm_detect_exec_unlink.c

[9] “KRSI PATCHv1.” [Online]. Available: https://lwn.net/ml/linux-kernel/20191220154208.15895-1-kpsingh@chromium.org/

[10] “KRSI PATCHv9 (final).” [Online]. Available: https://patchwork.kernel.org/project/linux-security-module/cover/20200329004356.27286-1-kpsingh@chromium.org/

[11] “KRSI RFCv1,” Oct. 09, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://lore.kernel.org/bpf/20190910115527.5235-1-kpsingh@chromium.org/#r

[12] “Linux Security Modules: General Security Support for the Linux Kernel”.

[13] “Linux Security Summit NA 2019: Kernel Runtime Security Instrumentation - KP Singh, Google,” Oct. 02, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CZSSRfgAgQ

[14] “Linux Security Summit NA 2020: KRSI (BPF + LSM) - Updates and Progress - KP Singh, Google,” Jul. 01, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://lssna2020.sched.com/event/c74F/krsi-bpf-lsm-updates-and-progress-kp-singh-google

[15] “LPC 2020: BPF LSM (Updates + Progress),” Aug. 25, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://lpc.events/event/7/contributions/680/

[16] “LWN: bpf: add ambient BPF runtime context stored in current.” https://lwn.net/Articles/862539/

[17] “LWN: Enabling Non-Executable Memfds.” https://lwn.net/Articles/918106/

[18] “LWN: Impedance Matching for BPF and LSM,” Feb. 26, 2020. https://lwn.net/Articles/813261/

[19] “LWN: Kernel Runtime Security Instrumentation.” https://lwn.net/Articles/798157/

[20] “LWN: KRSI — The Other BPF Security Module,” Dec. 27, 2019. https://lwn.net/Articles/808048/

[21] “LWN: KRSI and Proprietary BPF Programs,” Jan. 17, 2020. https://lwn.net/Articles/809841/

[22] “Mitigating Attacks on a Supercomputer With KRSI.”

[23] “[PATCH bpf-next 0/4] Reduce overhead of LSMs with static calls.” [Online]. Available: https://lore.kernel.org/bpf/202301201137.93A66D1C76@keescook/T/#ma6a93c345ad38764bef97c18c982c11ab1cf0c0f

[24] “[PATCH v4 bpf-next 00/20] Introduce BPF trampoline.” [Online]. Available: https://lore.kernel.org/bpf/20191114185720.1641606-1-ast@kernel.org/#t

[25] “[RFC] security: replace indirect calls with static calls.” [Online]. Available: https://lore.kernel.org/bpf/20200820164753.3256899-1-jackmanb@chromium.org/

[26] “Static Calls in Linux 5.10.” https://blog.yossarian.net/2020/12/16/Static-calls-in-Linux-5-10

[27] “The Design and Implementation of Userland Exec”, [Online]. Available: https://grugq.github.io/docs/ul_exec.txt

[28] “Volatility3.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/volatilityfoundation/volatility3